Here’s the pdf of the ppts for today’s workshop sponsored by Idaho State University.

Category Archives: Therapy with Adolescents

So-Called “Tough Kids” in Vermont: The PPTs

Hi All,

I’m virtually in Vermont tomorrow doing an all-day-long workshop on working with so-called challenging youth in counseling and psychotherapy. We start at 8am Mountain Time . . . and 10am on the East coast. Here’s the link to register for the workshop for anyone who suddenly has found themselves with a wide open day. The cost is: $195.

https://twinstates.ce21.com/item/tough-kids-cool-counseling-131540

And for those of you attending the workshop (or anyone who’s feeling nosy) here are the generic ppts (without the active video links):

Tough Kids, Cool Counseling — An Online Workshop – Dec 6, 2024

My wife (Rita) and I used to argue over who came up with the catchy “Tough Kids, Cool Counseling” title for our 1997/2007 book with the American Counseling Association. I would swear it was MY grand idea; she would swear back that it was HER idea. If any of you are in–or have been in–romantic partnerships, perhaps you can relate to disagreements over who has all the best ideas. I doubt that this dynamic is unique to Rita and me.

Years passed . . . and now I’ve come to very much dislike the title. . . leading me to give Rita ALL THE CREDIT! You’ve got it Rita! It was all you!

Despite my dislike for the title, I still sometimes use it for workshops. Why might that be, you may be wondering? Good question. I use it so I can make the point, early in the workshop, that we should NEVER use language that blames young people for their problems or their problem behaviors. In fact, we should never even “think” thoughts that assign blame to them for being “tough.”

My reasoning for this is informed by constructive theory and narrative therapy. When we assign blame and responsibility to young people for being “tough” or “difficult” or “challenging,” we risk contributing to them holding a tough, difficult, or challenging identity–which is exactly the opposite of what we want to be doing. Instead, I tell my workshop participants that we should recognize, there are no “tough kids” . . . there are only kids in tough situations . . . and being in counseling or psychotherapy is just another tough situation that young people have to face. Consequently, it’s NOT their fault if they engage in so-called tough or challenging behaviors.

All this leads me to share that I’ll be online all day on December 6, 2024, doing a workshop for mental health professionals. The workshop, anachronistically titled, “Tough Kids, Cool Counseling” is sponsored by the Vermont Psychological Association. You can register for the workshop here: https://twinstates.ce21.com/item/tough-kids-cool-counseling-131540

Even if I do say so myself, I’m proclaiming here and now that this will be a very engaging online workshop. If you work with youth (ages 10-18) in counseling or psychotherapy, and you need/want some year-ending CEUs, we’ll be having some virtual fun on December 6, and I hope you can join in.

Notes on My Favorite New Article

It can be good to have an IOU. I knew I owed my former student and current colleague, Maegan Rides At The Door, a chance to publish something together. We had started working on a project several years ago, but I got busy and dropped the ball. For years, that has nagged away at me. And so, when I read an article in the American Psychologist about suicide assessment with youth of color, I remembered my IOU, and reached out to Maegan.

The article, written by a very large team of fancy researchers and academics, was really quite good. But, IMHO, they neglected to humanize the assessment process. As a consequence, Maegan and I prepared a commentary on their article that would emphasize the relational pieces of the assessment process that the authors had missed. Much to our good fortune, after one revision, the manuscript was accepted.

I saw Maegan yesterday as she was getting the President Royce Engstrom Endowed Prize in University Citizenship award (yes, she’s just getting awards all the time). She said, with her usual infectious smile, “You know, I re-read our article this morning and it’s really good!”

I am incredibly happy that Maegan felt good about our published article. I also re-read the article, and felt similar waves of good feelings—good feelings about the fact that we were able to push forward an important message about working with youth of color. Because I know I now have your curiosity at a feverish pitch, here’s our closing paragraph:

In conclusion, to improve suicide assessment protocols for youth of color, providers should embrace anti-racist practices, behave with cultural humility, value transparency, and integrate relational skills into the assessment process. This includes awareness, knowledge, and skills related to cultural attitudes consistent with local, communal, tribal, and familial values. Molock and colleagues (2023) addressed most of these issues very well. Our main point is that when psychologists conduct suicide assessments, relational factors and empathic attunement should be central. Overreliance on standardized assessments—even instruments that have been culturally adapted—will not suffice.

And here’s the Abstract:

Molock and colleagues (2023) offered an excellent scholarly review and critique of suicide assessment tools with youth of color. Although providing useful information, their article neglected essential relational components of suicide assessment, implied that contemporary suicide assessment practices are effective with White youth, and did not acknowledge the racist origins of acculturation. To improve suicide assessment process, psychologists and other mental health providers should emphasize respect and empathy, show cultural humility, and seek to establish trust before expecting openness and honesty from youth of color. Additionally, the fact that suicide assessment with youth who identify as White is also generally unhelpful, makes emphasizing relationship and development of a working alliance with all youth even more important. Finally, acculturation has racist origins and is a one-directional concept based on prevailing cultural standards; relying on acculturation during assessments with youth of color should be avoided.

And finally, if you’re feeling inspired for even more, here’s the whole Damn commentary:

Strengths-Based Approaches to Management of Patient Suicidality

Today, I’m online doing the final webinar in a three-part series for PacificSource. The PacificSource organizers and participants have been fabulous. Everything has worked smoothly and the participants have engaged with many excellent thoughts and questions. We’ve got 503 registered for today.

Here’s the title and description of today’s webinar.

Strengths-Based Approaches to Management of Patient Suicidality

John Sommers-Flanagan, Ph.D.

Healthcare providers need to do more than conduct suicide assessments; they also need to flow from assessment into providing interventions to help patients move out of crisis and toward greater emotional regulation, hope, and health. In this webinar, using video clips and vignettes, you will learn at least five specific assessment and management interventions designed to help facilitate patient transitions from crisis to constructive problem-solving. These interventions are based on robust suicide theory, clinical wisdom, and empirical evidence on strategies for working effectively with patients who are suicidal.

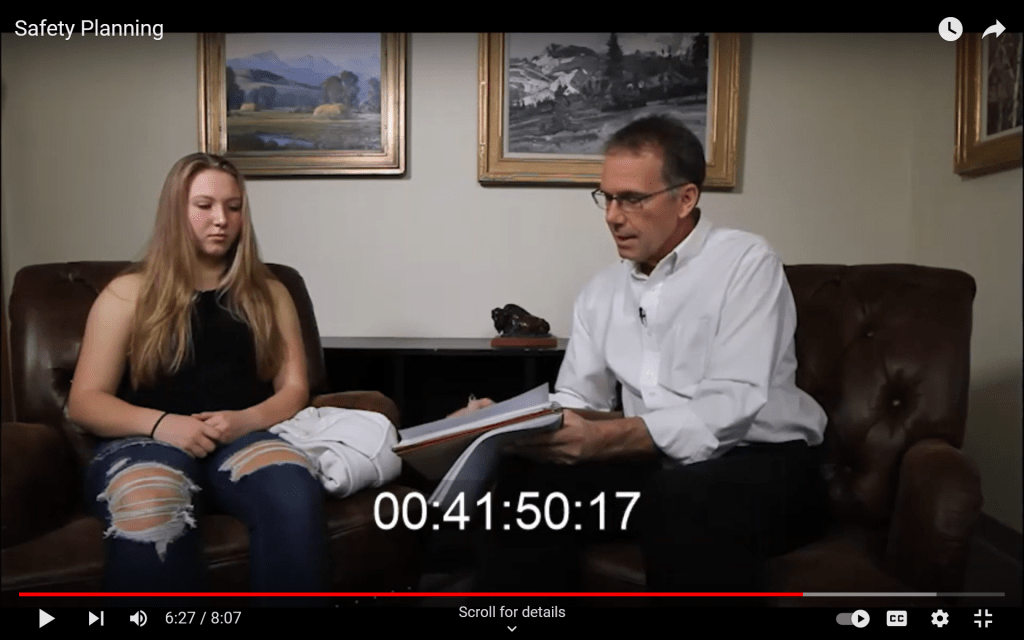

For anyone interested, here are the ppts for today:

The ppts also include two videos, one of which is linked below:

Riddles, Automatic Thoughts, Thinking Errors, Misattribution . . . and a Video Demonstration

Recently, I had the honor of presenting to Camp Mak-A-Dream residents (13-20 year-olds) on “Happiness and You.” To empower the residents—all of whom have experienced brain tumors—and resonate with the challenges of being human and having emotions, I shared the Three Step Emotional Change Technique. Then, I invited a volunteer to help me demonstrate how sometimes our brains can trick us by immediately providing the wrong answer to a question. A marvelous young man named Brandon stepped up and volunteered.

Here’s the video link, as recorded by Alli Bristow, last year’s Montana School Counselor of the Year (you can hear her reactions, which are pretty fun too):

You can watch the video, but I’m also sharing a description and rationale for the activities below.

The Riddle Activity

You’ll see me asking Brandon to respond to three riddles. I manage to trick him with the first one. For the second one, he’s briefly fooled, and then catches himself and gives the right answer. On the third, he pauses and gets the right answer the first time.

Why This Activity

I’ve used riddles like these in individual counseling with youth and in group presentations (as illustrated in the video). The riddle activity is all about a basic cognitive therapy message: If we go with our automatic thoughts, without pausing and evaluating them, we can be wrong. However, if we pause to evaluate the situational context and our reactive thoughts, sometimes we can override our automatic and possibly maladaptive impulses (Aaron and Judy Beck would be proud).

The Next Lesson

In the video, you only see Brandon and me doing the riddles. He’s great. When I’m doing this presentation (or using it in counseling) after the riddles, I immediately give the youth a situational example. I say something like, “Okay. Now let’s say I go to the same high school as Brandon, and I know him, and I’m walking by him in the hall at school. When I see him, I say ‘Hi Brandon!” But he just keeps on walking. What are my first thoughts?”

Whether I’m working with a group or with individuals, the young people are usually very good at suggesting possible immediate thoughts. They say things like: “You’re probably thinking he doesn’t like you.” Or, “Maybe you think he’s mad at you.”

At some point, I ask, “Have you ever said hello to someone and have them say nothing back?” There are always head nods and affirming responses.

Way back in our “Tough Kids, Cool Counseling” book, Rita and I wrote about the typical internalizing and externalizing responses that people tend to have in reaction to a possible social rejection. The internalizing response is depressed, anxious, and self-blaming. Internalizing thoughts usually take people down the track of “What did I do wrong” or “What’s wrong with me?” Alternatively, some youth have externalizing thoughts. Externalizing thoughts push the explanation outward, onto the other person. If you’re thinking externalizing thoughts, you’re thinking, “What’s wrong with him?” or “That jerk!” or “Next time, I’m not saying hi to him.” Back in the day, Kenneth Dodge wrote about externalizing thoughts in adolescents as contributing to aggression; he labeled this cognitive error “the misattribution of hostility.”

In counseling and in group presentations, the next step is to ask for neutral and non-blaming explanations for why Brandon didn’t say hello. The youth at Camp Mak-A-Dream were quick and efficient: “He probably didn’t hear you.” “Maybe he was having a bad day.” “He could have had his earbuds in.” “Maybe he was feeling shy?”

What’s the Point?

One goal of these activities is to help young people become more reflective and thoughtful. My neuroscience enthralled friends might say I’m working their frontal lobe muscles. I basically agree that whenever we can engage teens with thoughtful and reflective processes, they may benefit.

But the other goal may be even more important. Although I want to teach young people to be thoughtful, I also want to do that in the context of an engaging, sometimes fun, and interesting relationship. For me. . . it’s not just teaching and it’s not just learning. It’s teaching and learning in the crucible of a therapeutic relationship. As one of my former teen clients once said, “That’s golden.”

Let’s Do the “Three-Step” (Emotional Change Trick)

This morning’s weekly missive of “most read” articles from the Journal of the American Medical Association included a study evaluating the effects of high-dose “fluvoxamine and time to sustained recover in outpatients with COVID-19.” My reaction to the title was puzzlement. What could be the rationale for using a serotonin specific reuptake inhibitor for treating COVID-19? I read a bit and discovered there’s an idea and observations that perhaps fluvoxamine can reduce the inflammation response and prevention development of more severe COVID-19.

To summarize, the results were no results. Despite the fact that back in the 1990s some psychiatrists and pharmaceutical companies were campaigning for putting serotonin in the water systems, in fact, serotonin doesn’t really do much. As you know from last week, serotonin-based medications are generally less effective for depression than exercise.

For the happiness challenge this week, we’re touting the effectiveness of my own version of what we should put in the water or in the schools or in families—the Three-Step Emotional Change Trick. Having been in a several month funk over a variety of issues, I find myself returning to the application of the Three-Step Emotional Change Trick in my daily life. Does it always work? Nope. Is it better than feeling like a victim to my unpleasant thoughts and feelings? Yep.

I hope you’ll try this out and follow the instructions to push the process outward by sharing and teaching the three steps. Let’s try to get it into the water system.

Active Learning Assignment 9 – The 3-Step Emotional Change Trick

Almost no one likes toxic positivity. . . which is why I want to emphasize from the start, this week’s activity is NOT toxic positivity.

Back in the 1990s I was in full-time private practice and mostly I got young client referrals. When they entered my office, nearly all the youth were in bad moods. They were unhappy, sad, anxious, angry, and usually unpleasantly irritable. Early on I realized I had to do something to help them change their moods.

An Adlerian psychologist, Harold Mosak, had researched the emotional pushbutton technique. I turned it into a simple, three-step emotional change technique to help young clients deal with their bad moods. I liked the technique so well that I did it in my office, with myself, with parents, during professional workshops, and with classrooms full of elementary, middle, and high school students. Mostly it worked. Sometimes it didn’t.

This week, your assignment is to apply the three-step emotional change trick to yourself and your life. Here’s how it goes.

Introduction

Bad moods are normal. I would ask young clients, “Have you ever been in a bad mood?” All the kids nodded, flipped me off, or said things like, “No duh.”

Then I’d ask, “Have you ever had somebody tell you to cheer up?” Everyone said, “Yes!” and told me how much they hated being told to cheer up. I would agree and commiserate with them on how ridiculous it was for anyone to ever think that saying “Cheer up” would do anything but piss the person off even more. I’d say, “I’ll never tell you to cheer up.* If you’re in a bad mood, I figure you’ve got a good reason to be in a bad mood, and so I’ll just respect your mood.” [*Note to Therapists: This might be the single-most important therapeutic statement in this whole process.]

Then I’d ask. “Have you ever been stuck in a bad mood and have it last longer than you wanted it to?”

Nearly always there was a head nod; I’d join in and admit to the same. “Damn those bad moods. Sometimes they last and last and hang around way longer than they need to. How about I teach you this thing I call the three-step emotional change trick. It’s a way to change your mood, but only when YOU want to change your mood. You get to be the captain of your own emotional ship.”

Emotions are universally challenging. I think that’s why I never had a client refuse to let me teach the three-steps. And that’s why I’m sharing it with you now.

Step one is to feel the feeling. Feelings come around for a reason. We need to notice them, feel them, and contemplate their meaning. The big questions here are: How can you honor and feel your feelings? What can you do to respect your own feelings and listen to the underlying message? I’ve heard many answers. Here are a few. But you can generate your own list.

- Frowning or crying if you feel sad

- Grimacing and making angry faces into a mirror if you feel angry

- Drawing an angry picture

- Punching or kicking a pillow (no real violence though)

- Going outside and yelling (or screaming into a pillow)

- Scribbling on a note pad

- Writing a nasty note to someone (but not delivering it)

- Using your words, and talking to someone about what you’re feeling

Step two is to think a new thought or do something different. This step is all about intentionally doing or thinking something that might change or improve you mood. The big question here is: What can you think or do that will put you in a better mood?

I discovered that kids and adults have amazing mood-changing strategies. Here’s a sampling:

- Tell a funny story (“Yesterday in math, my friend Todd farted”)

- Tell a joke (What do you call it when 100 rabbits standing in a row all take one step backwards? A receding hare-line).

- Tell a better joke (Why did the ant crawl up the elephant’s leg for the second time? It got pissed off the first time.)

- Exercise!

- Smile into a mirror

- Talk to someone you trust

- Put a cat (or a chicken or a duck) on your head

- Chew a big wad of gum

I’m sure you get the idea. You know best what might put you in a good mood. When you’re ready, but not before, use your own self-knowledge to move into a better mood.

Step three is to spread the good mood. Moods are contagious. I’d say things like this to my clients:

“Emotions are contagious. Do you know what contagious means? It means you can catch emotions from being around other people who are in bad moods or good moods. Like when you got here. I noticed your mom was in a bad mood too. It made me wonder, did you catch the bad mood from her or did she catch it from you? Anyway, now you seem to be in a better mood. I’m wondering. Do you think you can make your mom “catch” your good mood?”

How do you share good moods? Saying “Cheer up” is off-limits. Here’s a short list of what I’ve heard from kids and adults.

- Do someone a favor

- Smile

- Hold the door for a stranger

- Offer a real or virtual hug

- Listen to someone

- Tell someone, “I love you”

Step four might be the best and most important step in the three-step emotional change trick. With kids, when I move on to step four, they always interrupt:

“Wait. You said there were only three steps!”

“Yes. That’s true. But because emotions are complicated and surprising, the three-step emotional change trick has four steps. The fourth step is for you to teach someone else the three steps.”

Here’s a youtube link to me doing the 3SECT: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ITWhMYANC5c

If you want to chase down an early version/citation, here’s a link for that: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1300/J019v17n04_02

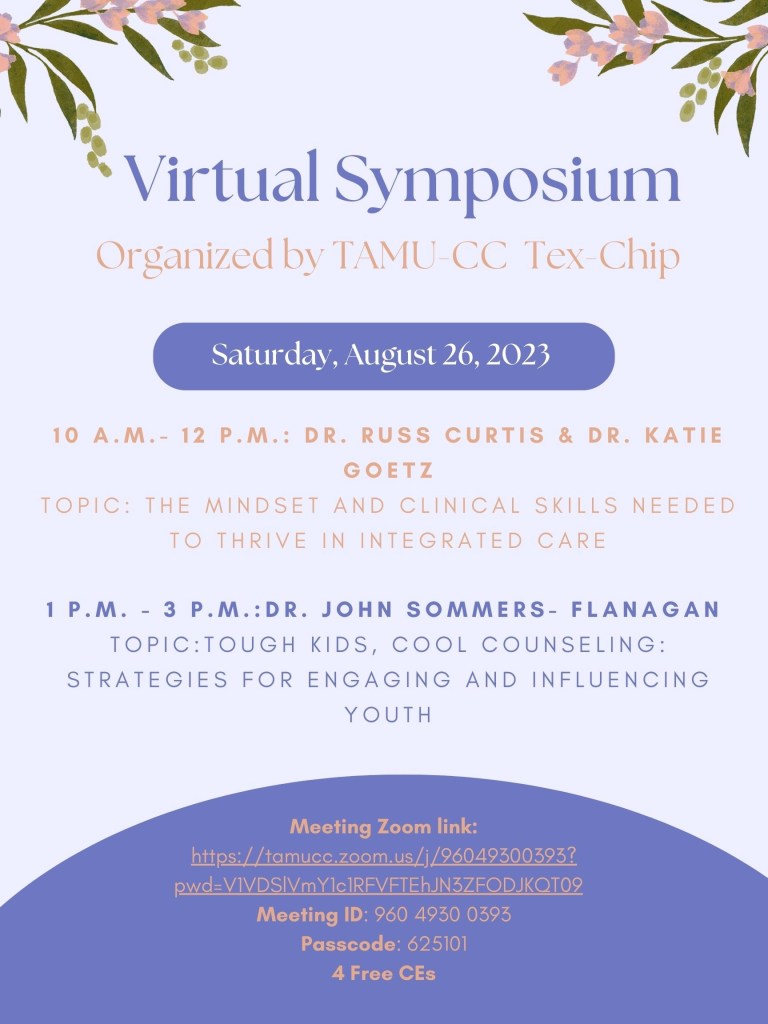

News Flash: Four FREE CEUs Coming Up This Saturday, August 26

As a part of a virtual symposium offered by Texas A&M University – Corpus Christi, this coming Saturday, August 26, I’m doing a 2-hour free continuing education workshop from 12-2pm Mountain time (2pm-4pm Eastern). The cool thing is that the CEUs for this workshop are FREE. The less cool thing is that the workshop is on a Saturday.

My talk is: Tough Kids, Cool Counseling: Strategies for Engaging and Influencing Youth. Even better, I’ll be preceded by Dr. Russ Curtis and Dr. Katie Goetz (9am-11am Mountain time), who are presenting a 2-hour workshop on The Mindset and Clinical Skills Needed to Thrive in Integrated Care. . . and that’s 2 more FREE CEUs.

Below, I’ve pasted the blurbs and Zoom information for these online workshops.

You are invited to join Tex-Chip Virtual Symposium on Saturday, August 26, 2023, at 10am – 3pm (CST).

Dr. Russ Curtis & Dr. Katie Goetz is scheduled to present from 10am – 12pm CST on “The Mindset and Clinical Skills Needed to Thrive in Integrated Care.” In this interactive presentation, participants will learn how to integrate clinical skills with enlightening philosophical premises to expand their understanding of providing inclusive whole-person care. Attendees will develop their clinical voice through lecture, case examples, and discussions to begin asking the right questions about how to provide next-generation integrated care.

Dr. Sommers-Flanagan is scheduled to present from 1pm – 3pm CST on “Tough Kids, Cool Counseling: Strategies for Engaging and Influencing Youth.” Engaging “tough kids” in behavioral health can be immensely frustrating or splendidly gratifying. The truth of this statement is so obvious that the supportive reference, at least according to many teenagers is “Duh!” In this 2-hour workshop, participants will learn, experience, and practice several strategies for engaging and influencing youth. Several cognitive, emotional, and constructive brief counseling techniques will be described and demonstrated. Examples include acknowledging reality, positive questioning, wishes and goals, the affect bridge, the three-step emotional change trick, what’s good about you?/asset flooding, and more. Essential counseling principles, countertransference, and cultural issues will be included.

Join Zoom Meeting

https://tamucc.zoom.us/j/96049300393?pwd=V1VDSlVmY1c1RFVFTEhJN3ZFODJKQT09

Meeting ID: 960 4930 0393

Passcode: 625101

For more information, please contact Ada at auzondu@islander.tamucc.edu

Tough Kids, Cool Counseling Visits Eastern Michigan

In 1990, when I moved back to Missoula, Montana to join Philip and Marcy Bornstein in their private practice, my goal was to establish a practice focusing on health psychology. I believed deeply in the body-mind connection and wanted to work with clients/patients with hypertension, asthma, and other health-related conditions with significant behavioral and psychosocial components.

Turns out, maybe because I was the youngest psychologist in town, all I got were referrals from Youth Probation Services, Child Protective Services, local schools, and parents who asked if I could “fix” their children’s challenging behaviors.

I’d say that I made lemonade from lemons, but it turns out I LOVED working with the so-called “challenging youth.” There were no lemons! The work led to our Tough Kids, Cool Counseling book (1997 and 2007), along with many articles, book chapters, and demonstration counseling videos. Over the years I’ve had the honor of working extensively with parents, families, youth, and young adults.

In about 10 days, I’ll be in Ypsilanti, Michigan doing a full-day professional workshop on “Tough Kids, Cool Counseling.” If you’re concerned about the title, don’t worry, so am I. In the first few minutes of the day, I’ll explain why using the terminology “Tough Kids” is a bad idea for counselors, psychotherapists, and other humans.

Just in case you’re in the Eastern Michigan area, the details and links for the conference are below. I hope to see you there . . . and hope if you make the trip, you’ll be sure to say hello to me at a break or after the workshop.

What: Tough Kids, Cool Counseling: Cognitive, Emotional, & Constructive Change Strategies

When: Friday, March 10, 2023, 8:30 AM – 5:00 PM EST

Where: Eastern Michigan University Student Center, Second Floor – Ballroom B Ypsilanti, MI 48197

Counseling so-called “tough kids” can be immensely frustrating or splendidly gratifying. The truth of this statement is so obvious that the supportive reference, at least according to many teenagers is, “Duh!” In this workshop, participants will sharpen their counseling skills by viewing and discussing video clips from actual counseling sessions, discussing key issues, and participating in live demonstrations. Attending this workshop will add tools to your counseling youth tool-box, and deepen your understanding of specific interventions. Over 20 cognitive, emotional, and constructive counseling techniques will be illustrated and demonstrated. Examples include acknowledging reality, informal assessment, the affect bridge, the three-step emotional change trick, asset flooding, empowered storytelling, and more. Four essential counseling principles, counselor counter-transference, and multicultural issues will be highlighted.

Strengths-Based Suicide Assessment and Treatment for the Youth Homes: The Powerpoints

Today I’m spending all day with the Youth Homes staff in Missoula . . . talking about strengths-based approaches to suicide. Should be fun, or at least as fun as a day of talking about suicide can be . . . Happy Friday, and here are the ppts!