Hi All,

Here are my slides for today. I hope you all have a fantastic Friday.

Hi All,

Here are my slides for today. I hope you all have a fantastic Friday.

On July 24, in Helena, I attended a fun and fascinating meeting sponsored by the Carter Center. I spent the day with a group of incredibly smart people dedicated to improving mental health in Montana.

The focus was twofold. How do we promote and establish mental health parity in Montana and how do with improve behavioral health in schools? Two worthy causes. The discussions were enlightening.

We haven’t solved these problems (yet!). In the meantime, we’re cogitating on the issues we discussed, with plans to coalesce around practical strategies for making progress.

During our daylong discussions, the term evidence-based treatments bounced around. I shared with the group that as an academic psychologist/counselor, I could go deep into a rabbit-hole on terminology pertaining to treatment efficacy. Much to everyone’s relief, I exhibited a sort of superhuman inhibition and avoided taking the discussion down a hole lined with history and trivia. But now, much to everyone’s delight (I’m projecting here), I’m sharing part of my trip down that rabbit hole. If exploring the use of terms like, evidence-based, best practice, and empirically supported treatment is your jam, read on!

The following content is excerpted from our forthcoming text, Counseling and Psychotherapy Theories in Context and Practice (4th edition). Our new co-author is Bryan Cochran. I’m reading one of his chapters right now . . . which is so good that you all should read it . . . eventually. This text is most often used with first-year students in graduate programs in counseling, psychology, and social work. Consequently, this is only a modestly deep rabbit hole.

Enjoy the trip.

*************************************

What Constitutes Evidence? Efficacy, Effectiveness, and Other Research Models

We like to think that when clients or patients walk into a mental health clinic or private practice, they will be offered an intervention that has research support. This statement, as bland as it may seem, would generate substantial controversy among academics, scientists, and people on the street. One person’s evidence may or may not meet another person’s standards. For example, several popular contemporary therapy approaches have minimal research support (e.g., polyvagal theory and therapy, somatic experiencing therapy).

Subjectivity is a palpable problem in scientific research. Humans are inherently subjective; humans design the studies, construct and administer assessment instruments, and conduct the statistical analyses. Consequently, measuring treatment outcomes always includes error and subjectivity. Despite this, we support and respect the scientific method and appreciate efforts to measure (as objectively as possible) psychotherapy outcomes.

There are two primary approaches to outcomes research: (1) efficacy research and (2) effectiveness research. These terms flow from the well-known experimental design concepts of internal and external validity (Campbell et al., 1963). Efficacy research employs experimental designs that emphasize internal validity, allowing researchers to comment on causal mechanisms; effectiveness research uses experimental designs that emphasize external validity, allowing researchers to comment on generalizability of their findings.

Efficacy Research

Efficacy research involves tightly controlled experimental trials with high internal validity. Within medicine, psychology, counseling, and social work, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the gold standard for determining treatment efficacy. RCTs statistically compare outcomes between randomly assigned treatment and control groups. In medicine and psychiatry, the control group is usually administered an inert placebo (i.e., placebo pill). In the end, treatment is considered efficacious if the active medication relieves symptoms, on average, at a rate significantly higher than placebo. In psychotherapy research, treatment groups are compared with a waiting list, attention-placebo control group, or alternative treatment group.

To maximize researcher control over independent variables, RCTs require that participants meet specific inclusion and exclusion criteria prior to random assignment to a treatment or comparison group. This allows researchers to determine with greater certainty whether the treatment itself directly caused treatment outcomes.

In 1986, Gerald Klerman, then head of the National Institute of Mental Health, gave a keynote address to the Society for Psychotherapy Research. During his speech, he emphasized that psychotherapy should be evaluated through RCTs. He claimed:

We must come to view psychotherapy as we do aspirin. That is, each form of psychotherapy must have known ingredients, we must know what these ingredients are, they must be trainable and replicable across therapists, and they must be administered in a uniform and consistent way within a given study. (Quoted in Beutler, 2009, p. 308)

Klerman’s speech advocated for medicalizing psychotherapy. Klerman’s motivation for medicalizing psychotherapy partly reflected his awareness of heated competition for health care dollars. This is an important contextual factor. Events that ensued were an effort to place psychological interventions on par with medical interventions.

The strategy of using science to compete for health care dollars eventually coalesced into a movement within professional psychology. In 1993, Division 12 (the Society of Clinical Psychology) of the American Psychological Association (APA) formed a “Task Force on Promotion and Dissemination of Psychological Procedures.” This task force published an initial set of empirically validated treatments. To be considered empirically validated, treatments were required to be (a) manualized and (b) shown to be superior to a placebo or other treatment, or equivalent to an already established treatment in at least two “good” group design studies or in a series of single case design experiments conducted by different investigators (Chambless et al., 1998).

Division 12’s empirically validated treatments were instantly controversial. Critics protested that the process favored behavioral and cognitive behavioral treatments. Others complained that manualized treatment protocols destroyed authentic psychotherapy (Silverman, 1996). In response, Division 12 held to their procedures for identifying efficacious treatments but changed the name from empirically validated treatments to empirically supported treatments (ESTs).

Advocates of ESTs don’t view common factors in psychotherapy as “important” (Baker & McFall, 2014, p. 483). They view psychological interventions as medical procedures implemented by trained professionals. However, other researchers and practitioners complain that efficacy research outcomes do not translate well (aka generalize) to real-world clinical settings (Hoertel et al., 2021; Philips & Falkenström, 2021).

Effectiveness Research

Sternberg, Roediger, and Halpern (2007) described effectiveness studies:

An effectiveness study is one that considers the outcome of psychological treatment, as it is delivered in real-world settings. Effectiveness studies can be methodologically rigorous …, but they do not include random assignment to treatment conditions or placebo control groups. (p. 208)

Effectiveness research focuses on collecting data with external validity. This usually involves “real-world” settings. Effectiveness research can be scientifically rigorous but doesn’t involve random assignment to treatment and control conditions. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for clients to participate are less rigid and more like actual clinical practice, where clients come to therapy with a mix of different symptoms or diagnoses. Effectiveness research is sometimes referred to as “real world designs” or “pragmatic RCTs” (Remskar et al., 2024). Effectiveness research evaluates counseling and psychotherapy as practiced in the real world.

Other Research Models

Other research models also inform researchers and practitioners about therapy process and outcome. These models include survey research, single-case designs, and qualitative studies. However, based on current mental health care reimbursement practices and future trends, providers are increasingly expected to provide services consistent with findings from efficacy and effectiveness research (Cuijpers et al., 2023).

In Pursuit of Research-Supported Psychological Treatments

Procedure-oriented researchers and practitioners believe the active mechanism producing positive psychotherapy outcomes is therapy technique. Common factors proponents support the dodo bird declaration. To make matters more complex, prestigious researchers who don’t have allegiance to one side or the other typically conclude that we don’t have enough evidence to answer these difficult questions about what ingredients create change in psychotherapy (Cuijpers et al., 2019). Here’s what we know: Therapy usually works for most people. Here’s what we don’t know: What, exactly, produces positive changes.

For now, the question shouldn’t be, “Techniques or common factors?” Instead, we should be asking “How do techniques and common factors operate together to produce positive therapy outcomes?” We should also be asking, “Which approaches and techniques work most efficiently for which problems and populations?” To be broadly consistent with the research, we should combine principles and techniques from common factors and EST perspectives. We suspect that the best EST providers also use common factors, and the best common factors clinicians sometimes use empirically supported techniques.

Naming and Claiming What Works

When it comes to naming and claiming what works in psychotherapy, we have a naming problem. Every day, more research information about psychotherapy efficacy and effectiveness rolls in. As a budding clinician, you should track as much of this new research information as is reasonable. To help you navigate the language of researchers and practitioners use to describe “What works,” here’s a short roadmap to the naming and claiming of what works in psychotherapy.

When Klerman (1986) stated, “We must come to view psychotherapy as we do aspirin” his analogy was ironic. Aspirin’s mechanisms and range of effects have been and continue to be complex and sometimes mysterious (Sommers-Flanagan, 2015). Such is also the case with counseling and psychotherapy.

Language matters, and researchers and practitioners have created many ways to describe therapy effectiveness.

Manuals, Fidelity, and Creativity

Manualized treatments require therapist fidelity. In psychotherapy, fidelity means exactness or faithfulness to the published procedure—meaning you follow the manual. However, in the real world, when it comes to treatment fidelity, therapist practice varies. Some therapists follow manuals to the letter. Others use the manual as an outline. Still others read the manual, put it aside, and infuse their therapeutic creativity.

A seasoned therapist (Bernard) we know recently provided a short, informal description of his application of exposure therapy to adult and child clients diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Bernard described interactions where his adult clients sobbed with relief upon getting a diagnosis. Most manuals don’t specify how to respond to clients sobbing, so he provided empathy, support, and encouragement. Bernard described a therapy scenario where the client’s final exposure trial involved the client standing behind Bernard and holding a sharp kitchen knife at Bernard’s neck. This level of risk-taking and intimacy also isn’t in the manual—but Bernard’s client benefited from Bernard trusting him and his impulse control.

During his presentation, Bernard’s colleagues chimed in, noting that Bernard was known for eliciting boisterous laughter from anxiety-plagued children and teenagers. There’s no manual available on using humor with clients, especially youth with overwhelming obsessional anxiety. Bernard used humor anyway. Although Bernard had read the manuals, his exposure treatments were laced with empathy, creativity, real-world relevance, and humor. Much to his clients’ benefit, Bernard’s approach was far outside the manualized box (B. Balleweg, personal communication, July 14, 2025).

As Norcross and Lambert (2018) wrote: “Treatment methods are relational acts” (p. 5). The reverse is equally applicable, “Relational acts are treatment methods.” As you move into your therapeutic future, we hope you will take the more challenging path, learning how to apply BOTH the techniques AND the common factors. You might think of this—like Bernard—as practicing the science and art of psychotherapy.

**********************************

Note: This is a draft excerpt from Chapter 1 of our 4th edition, coming out in 2026. As a draft, your input is especially helpful. Please share as to whether the rabbit hole was too deep, not deep enough, just right, and anything else you’re inspired to share.

Thanks for reading!

Last Friday night (or Saturday morning in South Korea), I had the honor and privilege of spending three hours online with 45 South Korean therapists. We were talking, of course, about strengths-based suicide assessment and treatment. Given my limited Korean language skills (is it accurate to say my language skills are limited if I can’t say or comprehend ANYTHING in Korean?), I had a translator. Although I couldn’t tell anything about the translation accuracy, my distinct impression was that she was absolutely amazing.

I had a friend ask how I happened to get invited to present to Korean therapists. My main response is that I believe the time is right (aka Zeitgeist) for greater integration of the strengths-based approach into traditional suicide assessment and treatment. The person who recruited me was Dr. Julia Park, another absolutely amazing, kind, and competent South Korean person, who also happens to hold an Adlerian theoretical orientation. Thanks Julia!

Just for fun, I wish I had my Korean translated ppts to share here. They’re unavailable, and so instead I’m sharing an excerpt from Chapter 10 (Suicide Assessment Interviewing) of our Clinical Interviewing (2024) textbook. The section I’m featuring is the part where we review issues and procedures around suicide risk categorization and decision-making.

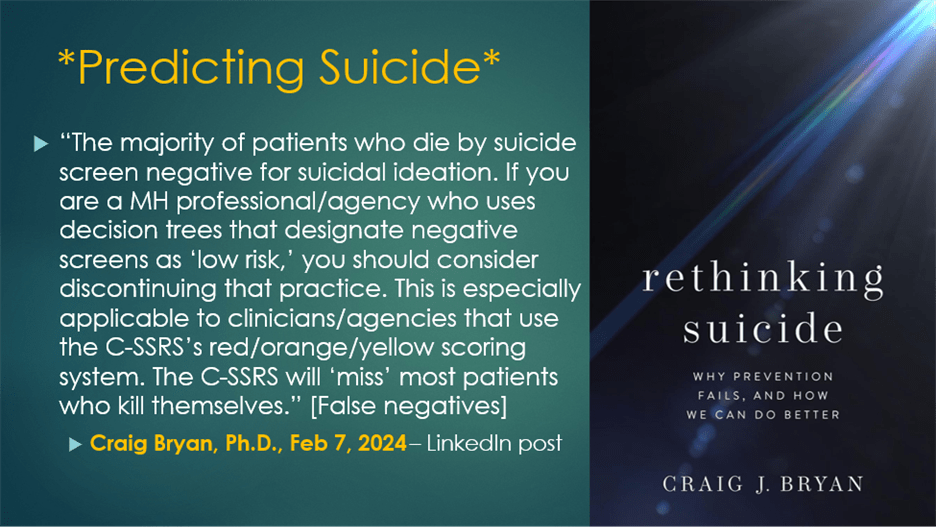

You may already know that some of the latest thinking on suicide risk assessment is that we should not use instruments like the Columbia to categorize risk. You also may know that not only am I a believer in this latest thinking, I can be wildly critical of efforts to categorize suicide risk. . . so much so that I often end up using profanity in my professional presentations. Of course, because the context is a professional presentation, I only use the highly professional versions of profanity.

Here’s a LinkedIn comment about that issue from Craig Bryan. Dr. Bryan is a suicide researcher, professor at The Ohio State University, and author of “Rethinking Suicide.” In support of him and his research and thinking, I’d like to professionally say that although I lean away from reductionistic categorization of things, all signs point to the likelihood that Dr. Bryan has a very large brain.

The good news is that I feel validated by Dr. Bryan’s strong comments against categorizing suicide risk. But the bad news is that we all live in the real world and in the real world sometimes professionals have to do more than just swear about risk categorization—we have to actually make recommendations for or against hospitalization, consult with other professionals who want our opinion, and quoting me as saying that risk factor categorization is pure bullshit may not be the best and most professional option.

So . . . what are we to do? First, we parse Dr. Bryan’s comments. He’s not saying NEVER categorize risk or make risk estimates. He’s saying don’t categorize “negative screens as low risk” which is slightly different than don’t try to estimate risk. His message is that we have too many false negatives—where someone screens negative and then dies by suicide. In other words, we should not be confident and say negative screens are “low risk.” That’s different from throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

It might be easy to think that Dr. Bryan’s comments are discouraging. But I view him as just saying we should be careful professionals. To help with that, below is the excerpt on Suicide risk categorization and decision-making, from our textbook. If you’re in a situation where you have to make a professional recommendation about suicide risk, this information may be helpful. BTW, the reason I was inspired to post this excerpt is because the Korean participants were wonderful and asked lots of hard questions, including questions related to this topic.

Consultation with peers and supervisors serves a dual purpose. First, it provides professional support; dealing with suicidal clients is difficult and stressful; input from other professionals is helpful. For your health and sanity, you shouldn’t do work with suicidal clients in isolation.

Second, consultation provides feedback about appropriate practice standards. Should you need to defend your actions and choices following a suicide death, you’ll be able to show you were meeting professional standards. Consultation is one way to monitor, evaluate, and upgrade your professional competency.

We reviewed an overwhelming number of suicide risk and protective factors earlier in this chapter. Generally, more risk factors equate to more risk. However, some risk factors are particularly salient. These include:

A previous attempt is sometimes viewed as suicide rehearsal. Two previous attempts are especially predictive of suicide because they represent repeated intent. Also, when previous attempts were severe and the client was disappointed not to die, risk is high.

When clients are experiencing a psychotic state accompanied by command hallucinations (e.g., a voice that says, “You must die’), risk is at an emergency level.

The combination of depression and agitation can be especially lethal. Agitation can take the form of extreme anxiety or extreme anger.

A single protective factor may outweigh many risk factors. But, it’s impossible to know the power of any individual protective factors without an in-depth discussion with your client. Engagement in therapy and collaboration on a safety plan (and the hope these behaviors signal) can substantially reduce risk.

As discussed earlier, suicidal ideation is evaluated based on frequency, triggers, intensity, duration, and termination. Some clients live chronically with high suicidal ideation frequency, intensity, and duration—and are low risk. However, if ideation is frequent and intense and accompanied by intent and planning, risk is high.

Suicide intent is the factor most likely to move clients toward lethal attempts. Intent can be based on objective or subjective signs. Objective signs of intent include one (or more) previous lethal attempt(s). Subjective signs of intent can include a client rating of intent or client report of a highly lethal plan.

How clients present themselves during sessions is revealing. Clients can be palpably hopeless, talk desperately about feelings of being trapped, and express painful and unremitting self-hatred or shame. But if clients have adapted to these experiences, they may not have accompanying intent and active planning. Observations of how clients talk about their psychological distress will contribute to your final decisions.

Using a traditional assessment approach, you can estimate your client’s suicide risk as fitting into one of three categories:

************************

As always, please share your thoughts in the comments on this blog.

Last week was a blur. On Wednesday, I did a break-out session for the Montana Prevent Child Abuse and Neglect conference in Helena. I’ve been to this conference multiple times and always deeply appreciate the amazing people in Montana and beyond who are dedicated to the mission of preventing child abuse and neglect. For the break-out, I presented on “Ten Things Everyone Should Know About Mental Health, Suicide, and Happiness.” This is one of my favorite newish topics and I felt very engaged with the 120+ participants. A big thanks to them.

Before the session, I felt a bit physically “off.” Overnight, the “off” symptoms developed into a sore throat and cough. This would NOT have been a problem, except I was scheduled for the hour-long closing conference keynote on Thursday. The good news is that I had zero fever and it was NOT Covid. The bad news was my voice was NOT good. I did the talk “In Pursuit of Eudaimonia” with 340ish attendees and got through it, but only with the assistance of a hot mic.

I had to cancel my Friday in Missoula and ended up in Urgent Care, with a diagnosis of bronchitis or possibly pneumonia, which was rather unpleasant over the weekend.

Having recovered (mostly), by yesterday, I recorded a podcast (Justin Angle’s “A New Angle” on Montana Public Radio) at the University of Montana College of Business. Thanks to a helpful pharmaceutical consult with a helpful woman at Albertsons, I had just the right amount of expectorant, later combined with a strong cough suppressant, to make it through 90 minutes of fun conversation with Justin without coughing into the podcast microphone. We talked about “Good Faith” in politics, society, and relationships. The episode will air in early June.

And now . . . I’m in beautiful Butte, Montana, where I’m doing an all-day (Thursday) workshop for the Montana Sex Offender Treatment Association. . . on Strengths-Based Suicide Assessment and Treatment . . . at the Copper King Hotel and Convention Center. Not surprisingly, having slept a bit extra the past five days, I’m up and wide awake at 4:30am, with not much to do other than post a pdf of my ppts for the day. Here they are:

Thanks for reading and thanks for being the sort of people who are, no doubt, doing what you can to make Montana and the world a little kinder and more compassionate place to exist.

Be well.

I’ve spent the better part of the past two weeks doing presentations in various locations and venues. I did five presentations in Nebraska, and found myself surprisingly fond of Lincoln and Kearney Nebraska. On Thursday I was at a Wellness “Reason to Live” conference with CSKT Tribal Services at Kwataqnuk in Polson. Just now I finished an online talk with the Tex-Chip program. One common topic among these talks was the title of this blog post. I have found myself interestingly passionate about the content of this particular. . . so much so that I actually feel energized–rather than depleted–after talking for two hours.

Not surprisingly, I’ve had amazingly positive experiences throughout these talks. All the participants have been engaged, interesting, and working hard to be the best people they can be. Beginning with the Mourning Hope’s annual breakfast fundraiser, extending into my time with Union Bank employees, and then being with the wonderful indigenous people in Polson, and finally the past two hours Zooming with counseling students in Texas . . . I have felt hope and inspiration for the good things people are doing despite the challenges they face in the current socio-political environment.

If you were at one of these talks (or are reading this post), thanks for being you, and thanks for contributing your unique gifts to the world.

For your viewing pleasure, the ppts for this talk are linked here.

For fans of Strengths-Based suicide workshops, this Friday I’m doing a three hour online workshop for the Western Oregon Mental Health Assocation.

The workshop is happening this Friday from 9-noon (PDT). It’s a pretty reasonable deal: $60 for licensed WOMHA members, $75 for licensed non-members, $35 for pre-licensed people, and $5 for students.

Sorry for the late notice, but here’s the link to register:

https://bookwhen.com/womha#focus=ev-s8as-20250411090000

And here’s a copy of the ppts:

I’m looking forward to my virtual trip back to Oregon this Friday!

This past week I had the honor and privilege of offering four presentations, one each on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday.

Monday was a Zoom date with a counseling class at West Virginia University.

Tuesday was an exciting in-person presentation for the University of Montana MOLLI program, kicking off our small group experiential Evidence-Based Happiness course for older adults. It was phenomenal. The older adults always bring it. One–among many–highlights was an 88 -year-old guy who, in the midst of the Three-Step Emotional Change Trick, shared about how he “Honored” his emotions by joining a grief group after his wife died (3 years ago). His sharing was beautiful and perfect.

Wednesday was my annual visit to Dr. Timothy Nichols’s Honors College course on LOVE. Dr. Nichols happens to be the Dean of the Honors College and one of the coolest and kindest and most enthused people on the planet. Mostly I go every year just to hear him introduce me. In truth, I also go because the topic and the students are INCREDIBLE. I think it may have been the best LOVE lecture EVER. I’d post the ppts here, but my computer crashed yesterday, and the U of M IT people (who are always very nice) are now attempting “data recovery.” Argh!

Thursday I got to hang out for two hours with the Graduate Students of the University of Montana Psychology Club. This was yet another fun experience with a group of students who are all simply brilliant. To top it off, a couple of my favorite people (and Psych faculty), Bryan Cochran and Greg Machek also attended. . . providing the precise level of sarcasm and humor that made the experience practically perfect. Here are the Psych Club’s ppts, which I happened to have on a flash drive:

I’ve been in repeated conversations with numerous concerned people about the risks and benefits of suicide screenings for youth in schools. Several years ago, I was in a one-on-one coffee shop discussion of suicide prevention with a local suicide prevention coordinator. She said, more as a statement than a question, “Who could be against school-based depression and suicide screenings?”

I slowly raised my hand, forced a smile, and confessed my position.

The question of how and why I’m not in favor of school-based mental health and suicide screenings is a complex one. On occasion, screenings will work, students at high-risk will be identified, and tragedy is averted. That’s obviously a great outcome. But I believe the mental health casualties from broad, school-based screenings tend to outweigh the benefits. Here’s why.

For more info on this, you can check out a brief commentary I published in the American Psychologist with my University of Montana colleague, Maegan Rides At The Door. The commentary focuses on suicide assessment with youth of color, but our points work for all youth. And, citations supporting our perspective are included.

Here are a few excerpts from the commentary:

Standardized questionnaires, although well-intended and sometimes helpful, can be emotionally activating and their use is not without risk (Bryan, 2022; de Beurs et al., 2016).

In their most recent recommendations, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (2022) concluded that the evidence supporting screening for suicide risk among children and adolescents was “insufficient” (p. 1534). Even screening proponents acknowledge, “There is currently little to no data to show that screening decreases suicide attempt or death rates” (Cwik et al., 2020, p. 255). . . . Across settings, little to no empirical evidence indicates that screening assessments provide accurate, predictive, or useful information for categorizing risk (Bryan, 2022).

And here’s the link to the commentary:

Hi All,

I’ve got two events coming up, one sooner and one later.

This Friday, I’m doing the closing talk for Tamarack’s Grief Institute (which is on Thursday and Friday in Missoula, and available online too!).

This is late notice, as the end of day tomorrow (March 3) is the registration deadline. The whole Institute is worth attending. The fantastic Dr. Joyce Mphande-Finn kicks things off on Thursday morning. Then, the amazing Dr. Micki Burns takes over . . . and I’ll be bringing it home Friday afternoon. Check it out. Here’s a registration link:

**********************

This June, I have the incredible fortune of joining Dr. Jeff Linkenbach and the renowned Montana Summer Institute in Big Sky, Montana (and Livestream) from June 17-20. Here’s a description of what’s happening!

Reimagining Community Health:

Uncovering Positive Norms and & Activating Hidden

Protective Factors

In Big Sky, Montana and via Livestream: June 17-20, 2025

Join us at the 2025 Montana Summer Institute for three and a half transformative days dedicated to advancing community well-being. Through thought-provoking keynotes, interactive workshops, and engaging discussions, you’ll explore innovative strategies that leverage positive norms and amplify protective factors.

Learn to uncover hidden community strengths, identify untapped opportunities, and craft impactful communications that drive meaningful change. With insights from leading experts and experienced practitioners, you’ll gain practical tools to reimagine your approach to data, messaging, and the people you serve—all through a positive, effective frame.

Don’t miss this opportunity to expand your expertise, deepen your impact, and shape healthier, more resilient communities. For more information, visit www.montanainstitute.com

Is there any chance you will join us in June? It would be wonderful to have you there! Here is the Montana Discount Code to give $100 off the price: MSIMONT which would give $100 off registration

***********************

And here’s a fancy flyer for the Montana Summer Institute:

The following is an excerpt from a chapter I wrote with my colleagues Roni Johnson and Maegan Rides At The Door. The full chapter is in the Cambridge Handbook of Clinical Assessment and Diagnosis . . .

*********************************

The clinical interview is a fundamental assessment and intervention procedure that mental and behavioral health professionals learn and apply throughout their careers. Psychotherapists across all theoretical orientations, professional disciplines, and treatment settings employ different interviewing skills, including, but not limited to, nondirective listening, questioning, confrontation, interpretation, immediacy, and psychoeducation. As a process, the clinical interview functions as an assessment (e.g., neuropsychological or forensic examinations) or signals the initiation of counseling or psychotherapy. Either way, clinical interviewing involves formal or informal assessment. [For a short video on how to address client problems and goals in the clinical interview, see below]

Clinical interviewing is dynamic and flexible; every interview is a unique interpersonal interaction, with interviewers integrating cultural awareness, knowledge, and skills, as needed. It is difficult to imagine how clinicians could begin treatment without an initial clinical interview. In fact, clinicians who do not have competence in using clinical interviewing as a means to initiate and inform treatment would likely be considered unethical (Welfel, 2016).

Clinical interviewing has been defined as

“a complex and multidimensional interpersonal process that occurs between a professional service provider and client [or patient]. The primary goals are (1) assessment and (2) helping. To achieve these goals, individual clinicians may emphasize structured diagnostic questioning, spontaneous and collaborative talking and listening, or both. Clinicians use information obtained in an initial clinical interview to develop a [therapeutic relationship], case formulation, and treatment plan” (Sommers-Flanagan & Sommers-Flanagan, 2017, p. 6)

A Generic Clinical Interviewing Model

All clinical interviews follow a common process or outline. Shea (1998) offered a generic or atheoretical model, including five stages: (1) introduction, (2) opening, (3) body, (4) closing, and (5) termination. Each stage includes specific relational and technical tasks.

Introduction

The introduction stage begins at first contact. An introduction can occur via telephone, online, or when prospective clients read information about their therapist (e.g., online descriptions, informed consents, etc.). Client expectations, role induction, first impressions, and initial rapport-building are central issues and activities.

First impressions, whether developed through informed consent paperwork or initial greetings, can exert powerful influences on interview process and clinical outcomes. Mental health professionals who engage clients in ways that are respectful and culturally sensitive are likely to facilitate trust and collaboration, consequently resulting in more reliable and valid assessment data (Ganzini et al., 2013). Technical strategies include authentic opening statements that invite collaboration. For example, the clinician might say something like, “I’m looking forward to getting to know you better” and “I hope you’ll feel comfortable asking me whatever questions you like as we talk together today.” Using friendliness and small talk can be especially important to connecting with diverse clients (Hays, 2016; Sue & Sue, 2016). The introduction stage also includes discussions of (1) confidentiality, (2) therapist theoretical orientation, and (3) role induction (e.g., “Today I’ll be doing a diagnostic interview with you. That means I’ll be asking lots of questions. My goal is to better understand what’s been troubling you.”). The introduction ends when clinicians shift from paperwork and small talk to a focused inquiry into the client’s problems or goals.

Opening

The opening provides an initial focus. Most mental health practitioners begin clinical assessments by asking something like, “What concerns bring you to counseling today?” This question guides clients toward describing their presenting problem (i.e., psychiatrists refer to this as the “chief complaint”). Clinicians should be aware that opening with questions that are more social (e.g., “How are you today?” or “How was your week?”) prompt clients in ways that can unintentionally facilitate a less focused and more rambling opening stage. Similarly, beginning with direct questioning before establishing rapport and trust can elicit defensiveness and dissembling (Shea, 1998).

Many contemporary therapists prefer opening statements or questions with positive wording. For example, rather than asking about problems, therapists might ask, “What are your goals for our meeting today?” For clients with a diverse or minority identity, cultural adaptations may be needed to increase client comfort and make certain that opening questions are culturally appropriate and relevant. When focusing on diagnostic assessment and using a structured or semi-structured interview protocol, the formal opening statement may be scripted or geared toward obtaining an overview of potential psychiatric symptoms (e.g., “Does anyone in your family have a history of mental health problems?”; Tolin et al., 2018, p. 3).

Body

The interview purpose governs what happens during the body stage. If the purpose is to collect information pertaining to psychiatric diagnosis, the body includes diagnostic-focused questions. In contrast, if the purpose is to initiate psychotherapy, the focus could quickly turn toward the history of the problem and what specific behaviors, people, and experiences (including previous therapy) clients have found more or less helpful.

When the interview purpose is assessment, the body stage focuses on information gathering. Clinicians actively question clients about distressing symptoms, including their frequency, duration, intensity, and quality. During structured interviews, specific question protocols are followed. These protocols are designed to help clinicians stay focused and systematically collect reliable and valid assessment data.

Closing

As the interview progresses, it is the clinician’s responsibility to organize and close the session in ways that assure there is adequate time to accomplish the primary interview goals. Tasks and activities linked to the closing include (1) providing support and reassurance for clients, (2) returning to role induction and client expectations, (3) summarizing crucial themes and issues, (4) providing an early case formulation or mental disorder diagnosis, (5) instilling hope, and, as needed, (6) focusing on future homework, future sessions, and scheduling (Sommers-Flanagan & Sommers-Flanagan, 2017).

Termination

Termination involves ending the session and parting ways. The termination stage requires excellent time management skills; it also requires intentional sensitivity and responsiveness to how clients might react to endings in general or leaving the therapy office in particular. Dealing with termination can be challenging. Often, at the end of an initial session, clinicians will not have enough information to establish a diagnosis. When diagnostic uncertainty exists, clinicians may need to continue gathering information about client symptoms during a second or third session. Including collateral informants to triangulate diagnostic information may be useful or necessary.

See the 7th edition of Clinical Interviewing for MUCH more on this topic:

https://www.wiley.com/en-sg/Clinical+Interviewing%2C+7th+Edition-p-9781119981985