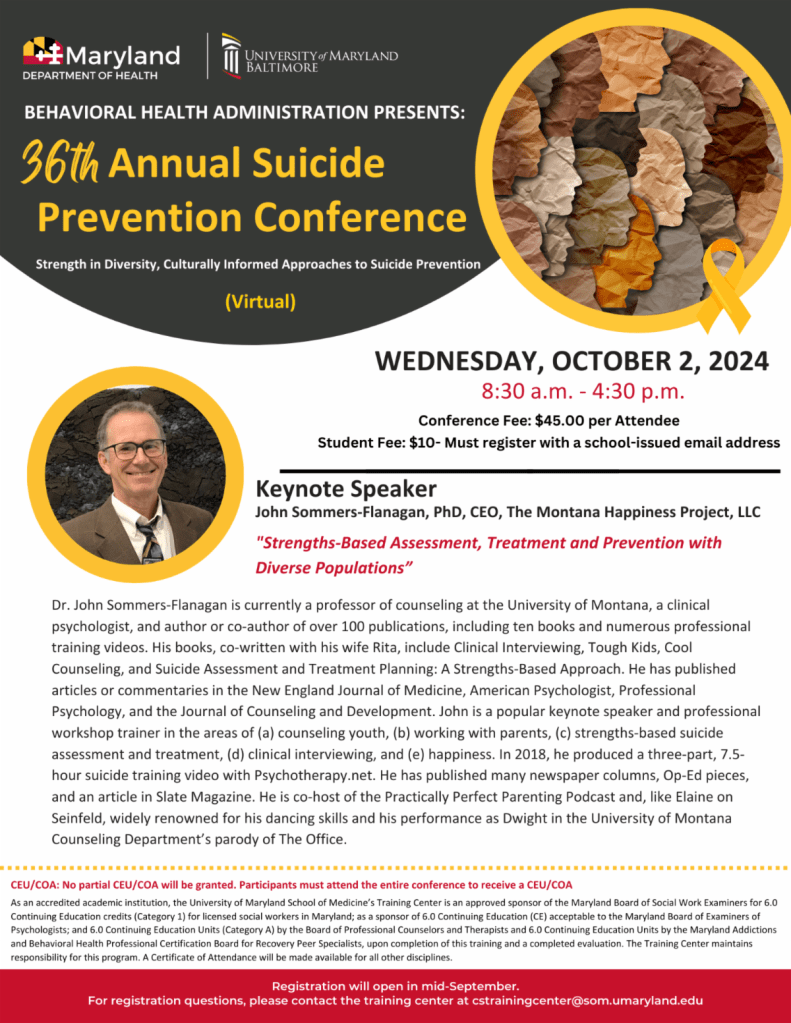

Tomorrow’s talk is titled, Ten Things Everyone Should Know About Children’s Mental Health and Happiness. Because this talk is about what everyone should know, I suspect everyone will be there. So, I’ll see you soon.

Given the possibility that everyone won’t be there, I’m sharing the list of the 10 things, along with some spiffy commentary.

First, I’ll give a strength warning. If you don’t know what that means, you’re not alone, because I made it up. It might be the coolest idea ever, so watch for more details about it in future blogs.

Then, I’ll say something profound like, “The problems with mental health and happiness are big, and they seem to just be getting bigger.” At which point, I’ll launch into the ten things.

- Mental health and happiness are wicked problems. This refers to the fact that mental health and happiness are not easy to predict, control, or influence. They’re what sociologists call “wicked problems,” meaning they’re multidimensional, non-linear, elicit emotional responses, and often when we try to address them, our well-intended efforts backfire.

- Three ways your brain works. [This one thing has three parts. Woohoo.]

- We naturally look for what’s wrong with us. Children and teens are especially vulnerable to this. In our contemporary world they’re getting bombarded with social media messages about diagnostic criteria for mental disorders so much that they’re overidentifying with mental disorder labels.

- We find what we’re looking for. This is called confirmation bias, which I’ve blogged about before.

- What we pay attention to grows. This might be one of the biggest principles in all of psychology. IMHO, we’re all too busy growing mental disorders and disturbing symptoms (who doesn’t have anxiety?).

- We’re NOT GOOD at shrinking NEGATIVE behaviors. This is so obvious that my therapist friends usually say, “Duh” when I mention it.

- We’re better at growing POSITIVE behaviors. Really, therapy is about helping people develop skills and strengths for dealing with their symptoms. More skills, strengths, and resources result in fewer disturbing symptoms.

- Should we focus on happiness? The answer to this is NO! Too much preoccupation with our own happiness generally backfires.

- What is happiness? If you’ve been following this blog, you should know the answer to this question. Just in case you’re blanking, here’s a pretty good definition: From Aristotle and others – “That place where the flowering of your greatest (and unique) virtues, gifts, skills, and talents intersect (over time) with the needs of the world [aka your family/community].”

- You can flip the happiness. This thing flows from a live activity. To get it well, you’ll need to be there!

- Just say “No” to toxic positivity. To describe how this works and why we say no to toxic positivity, I’ll take everyone through the three-step emotional change trick.

- Automatic thoughts usually aren’t all that positive. How does this work for you? When something happens to you in your life and your brain starts commenting on it, does your brain usually give you automatic compliments and emotional support? I thought not.

- How anxiety works. At this point I’ll be fully revved up and possibly out of time, so I’ll give my own anxiety-activated rant about the pathologizing, simplistic, and inaccurate qualities of that silly “fight or flight” concept.

Depending on timing, I may add a #11 (Real Mental Health!) and close with my usual song.

For those interested, here’s the slide deck:

If you’re now experiencing intense FOMO, I don’t blame you. FOMO happens. You’ll just need to lean into it and make a plan to attend one of my future talks on what everyone should know.

Thanks for reading and have a fabulous evening. I’ll be rolling out of Absarokee on my way to Butte at about 5:30am!