All posts by johnsommersflanagan

Strength-based Strategies for Educator Well-being: Research & Results — A Guest Blog

A guest blog by Tavi Brandenburg, with Hyrum Booth and Beth Loudon

**JSF Note: Below you’ll find a guest blog piece from Tavi Brandenburg. Tavi is a doctoral student in Counseling and Supervision at the University of Montana. The blog piece is a summary of themes she, Hyrum, and Beth (two more doc students), derived from a qualitative study of educator responses to our Happiness for Educators course. The themes are in Bold. As you may know, the HFE course is a 3-credit asynchronous course offered through the University of Montana. I hope you enjoy this “Amazing” summary. I am grateful to Tavi, Hyrum, and Beth for their support of our HFE course.**

For the past several months, Hyrum Booth, Beth Loudon, and I (Tavi Brandenburg) have been working on many levels of the Evidence-based Happiness for Educators Course (COUN 591) offered through CAPE & UM. We had the good fortune to share a bit about the course and our findings at the Association of Counselor Educators and Supervisors in Philadelphia. Here’s a link to the presentation slide deck:

Hyrum and I conducted 38 interviews. We enjoyed immersing ourselves in the interview transcripts to make sense of what the participants shared. We asked questions about the lasting impressions of the course, how the participants applied and continue to apply the evidence-based strategies presented during the course, and we asked about the lasting effects of the course on their personal and professional lives. While not always simple and straightforward, the qualitative results–the stories we collected–indicated positive impressions of the course, continued application of the strength-based strategies, and positive ongoing effects personally and interpersonally. And it was much more than that; the participants shared stories that illustrate deep fundamental shifts in personal wellbeing that have lasted over time. The course caused a ripple effect.

As with any ripple effect, there is a catalyst for change–a pebble, a stone, a boulder–for Montana Educators. This course acted as a catalyst for change, sending participants in the direction of introspection and personal development. Most participants experienced some level of dissonance due to discrepancies between their motivations for signing up for the course, including movement on the pay scale, inexpensive continuing education credits, preconceived notions of the course or content based on what they had heard from others. This dissonance was also related to course structure, expectations, and the responsive feedback they received. The personal nature of the course caught many off guard. The flexibility offered in the course design provided autonomy and allowed participants to select evidence-based practices that were meaningful to them rather than progressing through a set of prescribed exercises that may not resonate. This dissonance also came up for folks when the content felt too close to home. When participants experienced personally challenging life events and the course simultaneously, they tended to have strong reactions to either the material, the activities, the pace, or amount of material in the course. As a result of the dissonance they experienced, participants tended to give themselves permission for self-care, which allowed greater ‘flow’ within their professional and personal lives. Additionally, some participants described wide ranging content from more approachable concepts like developing tiny habits, to emotionally challenging exercises like experimenting with forgiveness. For some, the breadth of the content coupled with the pace of the course felt too much at once.

While engaging with the content, participants experienced vulnerability. Depending on the level of depth participants allowed themselves to go while completing the evidence-based practices, vulnerability challenged participants’ sense of comfort; it is not always easy to look inward. Vulnerability also contributed to meaningful connections with family members, colleagues, and students. Vulnerability led to increased self-awareness and other-awareness, and empathy.

Participants articulated being able to be more mindfully present in their daily tasks ranging from doing the dishes, to grading papers, to the quality of engagement with loved ones and learning communities. Vulnerability and presence gave way for some to take important, life-changing steps in their lives. For some, this meant increased ability to set boundaries around work or areas in their lives that they historically struggled to say ‘no,’ allowing these folks to maintain energy for themselves and their own wellbeing or a deepened state of connection with loved ones. Several participants took radical steps to prioritize themselves by leaving relationships or K-12 education. These folks specifically stated the course did not cause these substantial changes, rather the course illuminated a way of being that was more in line with how they would like to live their lives and they had the presence of mind to execute momentous changes.

Another ripple created by taking the courses includes the development and/or reinforcement of a wellbeing toolkit that they used for themselves and shared with loved ones and learning community members. Many participants took evidence-based exercises from the course and directly and intentionally applied them in their lives, with their families, with their students, and in their learning communities. Some teachers reported marked improvement in the classroom community, noting that students were more engaged in their learning, more empathic with others, more willing to take intellectual risks (be vulnerable). Many participants noted incorporating gratitude into their daily lives at home, and at school. Often professional development is a ‘top down’ experience, leaving teachers struggling to connect with the ‘why’ of new practices. This course, as professional development, had the opposite effect. Teachers applied the practices and developed a wellbeing toolkit that worked for them, leading them to deeply know the importance of strength-based practices. The autonomy created by the course structure allowed for creativity, authenticity, and agency in how educators incorporated the material into their personal and professional lives. Educators incorporated strengths-based concepts into a variety of subject areas, from Special Ed to Ed. Leadership to all levels and subjects in the classroom, to School Counseling, and beyond.

Participants felt like this course and content was so meaningful they advocated on many levels, took on leadership with the content (arranging guest speakers, joining John to advocate for CAPE, sharing the fliers with colleagues, family members also in education, whole districts). Some advocated at the district leadership level by advocating for trickle down happiness. We know that students are happier when their teachers are happier. The connection with others through the course helped educators feel less professionally isolated. This sense of connection led many participants to advocate for the course and improve mental health for others in the community.

We interviewed participants who had taken the course anywhere from four months to about one and a half years prior to the interview. While many participants stated they use their wellbeing toolkit as needed, especially as they encounter new challenges, we also heard participants refer to their notes during the interview, wishing they had periodic reminders about the content; many kept their folders handy. This indicates a quality of evanescence. Participants’ connections with the content faded over time, and there seemed to be genuine interest in a second level, or some means of continuing to regularly connect with the content.

We sought to understand the lasting effect, the applications, and the lingering memories participants had from the course. What we found, however, was a ripple of themes that illustrate the deep and meaningful change that is possible when people are provided with strengths-based information and an invitation to engage in self-reflective activities; the participants connected with agency resulting in improved mental and physical health. Amazing.

Slides for Idaho State University

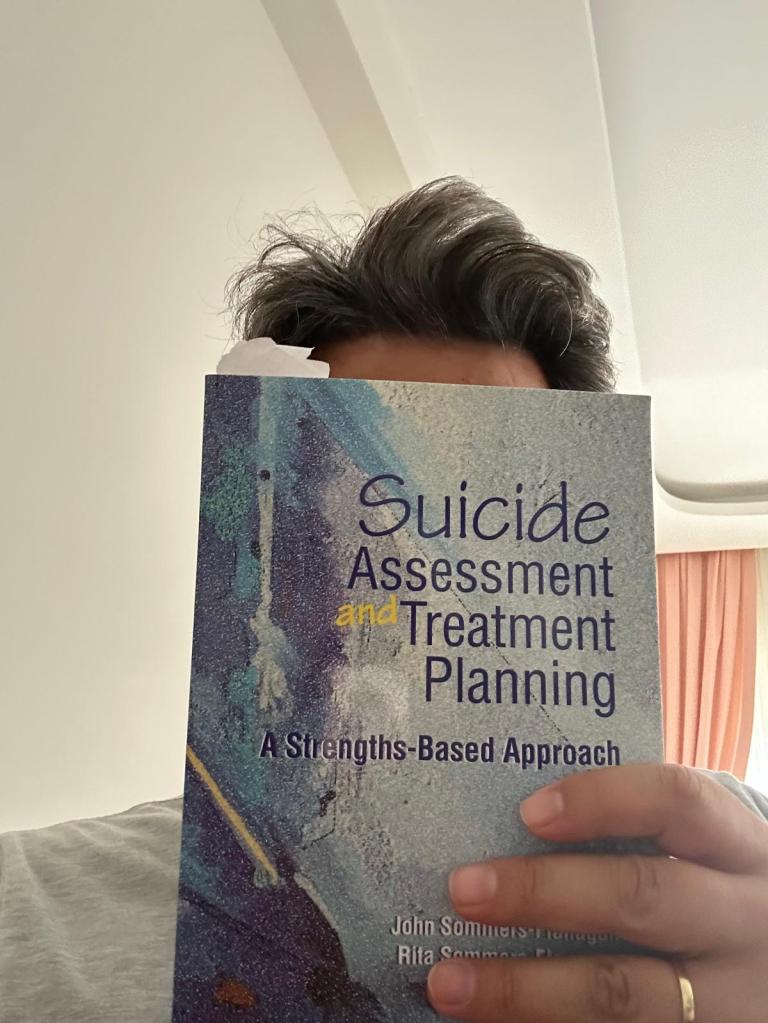

A Glimpse and Quote from Laura Perls (co-developer of Gestalt Therapy) . . . and the Suicide Prevention Slides for North Carolina State University

You may be wondering (I know I am), what does a glimpse and quote from the illustrious Laura Perls have to do with suicide prevention slides for North Carolina State University?

If you have thoughts on the connection, please share. I see a connection, but maybe it’s just because I wanted to post both these things. First, here’s a bit of content from Laura Perls from our Counseling and Psychotherapy Theories text.

***************************************

Although the contributions of Laura Posner Perls to Gestalt therapy practice were immense, she never receives much credit, partly due to the flamboyant extraversion of Fritz and partly because her name, somewhat mysteriously (at least to us), is not on many publications. She does, however, comment freely on Fritz’s productivity at the twenty-fifth anniversary of the New York Institute for Gestalt Therapy (an organization that she co-founded with Fritz).

Without the constant support from his friends, and from me, without the constant encouragement and collaboration, Fritz would never have written a line, nor founded anything. (L. Perls, 1990, p. 18)

REFLECTIONS

We hear resentment in the preceding quotation from Laura Perls. We feel it too, because we’d like to know more about Laura and for her to have gotten the credit she deserved. If you want more Laura, here’s a nice tribute webpage: https://gestalt.org/laura.htm?ya_src=serp300. And here’s a quotation from her (obtained from the webpage and compiled by Anne Leibig): “Real creativeness, in my experience, is inextricably linked with the awareness of mortality. The sharper this awareness, the greater the urge to bring forth something new, to participate in the infinitely continuing creativeness in nature. This is what makes out of sex, love; out of the herd, society; out of wheat and fruit, bread and wine; and out of sound, music. This is what makes life livable and incidentally makes therapy possible.”

Now, don’t you want to hear more from Laura?

*******************************************

And here’s the North Carolina State University link:

Toasting the End of Gratitude (Weekend)

On this weekend, when there is so much wrong in the world, it may be more important than ever for us to gather in small groups, pause, focus on what’s right and good, and express gratitude.

How’s that going? Are you feeling the gratitude?

Often, focusing on what’s right, on good things, and on strengths and solutions, takes effort. It’s not easy to orient our brains to what’s right, even in the best of times.

As negativity rains down on and around us through news and social media, it’s easy to get judgy. And when I say “judgy” I don’t mean judgy in a nice, positive, “I love your shoes” or “You have such creative views on immigrants” sort of way. Shifting our brains from their natural focus on angst and anger to gratitude feels difficult and sometimes impossible.

First Toast: Let’s hear it for the forces outside and inside ourselves that make it REALLY DIFFICULT to FEEL gratitude, hope, and positivity.

[Editor’s note: When I’m suggesting we push ourselves to experience gratitude and focus on strengths, I’m not endorsing toxic positivity. Sometimes we all need to rant, rave, complain, and roll around in the shit. If that’s what you need, you should find the time, place, and space to do just that. What I’m suggesting here is that opening yourself up to experiencing gratitude and focusing on strengths and solutions is like a muscle. If we intentionally give it a workout, it can get stronger. But, if you’re not ready for or interested in a positivity workout, don’t do it!]

Second Toast: How about some cheer for the EFFORT it takes to push ourselves to focus on gratitude, hope, strengths, and solutions—because that’s how we grow them. Woohoo!

Earlier this year, I attended a medical conference where the presenter did an exquisite job describing the “problem-solving model.” Having taught about problem-solving for three decades, my mind wandered, until the presenter—who was excellent by the way—passionately stated, “Before moving forward, before doing anything, we need to define the problem!”

Maybe it was just me being oppositional, but my wandering mind suddenly became woke and whispered something sweet in my inner ear, like, “This might be bullshit.”

I found myself face-to-face with the BIG problem with problem-solving.

You may be wondering, “What is the BIG problem with problem-solving?” Thanks for wondering. The problem includes:

- As my colleague Tammy says, maybe we don’t need to gather round and worship the problem.

- When we drill deeper and more meticulously into what’s wrong, we can grow the problem.

- As social constructivist theorists would say, “When we center the problem in our collective psyches,” we give it mass, and make it more difficult to change.

What if, instead of relentlessly focusing on the problem, we decided to only discuss what’s going well and possible solutions? What if we decided to grow and celebrate good things?

Adopting a mental set to persistently focus on strengths and solutions is not a new idea. Back in the 1980s, Insoo Kim Berg and Stephen de Shazer pushed as, “Solution-focused brief therapy” (SFBT).

At the time, I found their ideas interesting, but not captivating. One of my friends and a champion for all things strengths-focused (you know who you are Jana), knew the famous Insoo Kim Berg. Once, as Jana and I brainstormed, the possibility of consulting with Insoo came up. Jana said something like, “I could reach out to her, but if we frame this as a problem, Insoo might not even understand what we’re talking about. Insoo only speaks the language of solutions.”

Third Toast: Let’s toast Jana and Insoo Kim Berg for inspiring me to suddenly remember a conversation from 25 years ago.

The language of problems has deep roots in our psyche. Of course it does. Evolutionary psychology people would say we had to notice and orient toward problems to survive, and so we passed problem-focused genes onto offspring. As our brains evolved, they became excellent at identifying problems, because if we didn’t quickly identify problems, threats, or danger, we would be dead.

[Editor’s note: In contrast to biological evolution theory, evolutionary psychology is incredibly fun, but not very scientific. I know I’m supposed to be orienting myself to the positive right now, but evolutionary psychology mostly involves creating contemporary explanations for observed patterns from the past. As you can imagine, it’s quite entertaining and easy to make up fascinating explanations for human behavior, especially if you don’t need to reconcile your creative ideas with anything resembling fossilized evidence.]

Fourth Toast: Hat’s off and glasses up to evolutionary psychology for aptly demonstrating the power of social constructionism. Boom!

Most of us are naturally well-versed in the language of problems. We see them. We expect them. Even when no problems are present, we worry they’re coming. And they are. Problems and catastrophes are always on their way.

But most of us are not especially well-versed in Insoo Kim Berg’s language of strengths and solutions. Becoming linguistically fluent in strengths and solutions requires effort, discipline, and practice. How could it be any other way? If we WANT to speak the language of the positive, we need to learn and practice it; immersion experiences can be especially helpful.

As our collective gratitude weekend ends, we might benefit from committing ourselves to practicing the language of the positive. We could strive to become so linguistically positive that, at night, we begin dreaming in solution-focused, strengths-based language.

Fifth Toast: Let’s raise our glasses to dreaming in bright, colorful strengths.

We shouldn’t forget our old, natural, first language of problems. Problem-focused language is essential to survival and progress. We just need to stretch ourselves and become bilingual. Imagine the benefits for individuals, families, communities, and nations when we become intentionally bilingual, moving beyond the problem saturated language of our times, and into a solution-saturated future.

Last Toast: Three cheers to you, for making it to the end of this blog. May you have a glorious gratitude-filled holiday weekend.

John SF

The Invention of the Strength Warning

Now that I’m immersed in positivity every day as the Director of the Center for the Advancement of Positive Education, I think I’ve become weirder.

Some of you, including my sisters and brothers-in-law may be wondering, “Wait. How could John become any MORE weird than he already is?”

You know what they say: “All things are possible!” [Actually, I don’t know why I just wrote all things are possible, because, even in my most positive mental states, I don’t believe that BS. All things are not possible. I could make a list of impossible things, but I’ve already digressed.]

Here’s what I mean by me becoming even weirder.

I find myself more easily hearing and seeing the pervasive negative narratives emerging around us. I could make another long list of all the bad ideas (negative narratives) I’m noticing (think: “fight or flight”), but I’ll limit myself to one example: The “Trigger warning.”

Trigger warnings are statements that alert listeners or viewers (or people attending my suicide assessment workshops) to upcoming intense and potentially emotionally activating content. Over the past 10ish years, we’ve all started giving and receiving trigger warnings from time to time, now and then. A specific example, “The next segment of this broadcast includes gunfire” or “In my lecture I will be talking about mental health and suicide.”

As a college professor in a mental health-related discipline, I became well-versed in providing trigger warnings. . . and have offered them freely. Because some people have strong and negative emotional reactions to specific content, providing trigger warnings has always made good sense. The point is to alert people to intense content so they can take better care of themselves or opt out (stop listening/viewing). Trigger warnings are important and, no doubt, useful for helping some people prepare for emotionally activating content.

As a college professor, I’m also obligated to keep up with the latest research. Unfortunately, the research on trigger warnings isn’t very supportive of trigger warnings. Argh! In general, it appears that trigger warnings sensitize people and might make some people more likely to have a negative emotional response. You can read a 2024 meta-analysis on trigger warning research here: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/21677026231186625

In response to the potential adverse effects of trigger warnings, I came up with a clever idea: I started giving trigger warnings for my trigger warnings. These were something like, “Because research suggests that trigger warnings can make you more reactive to negative content, I want to give you a trigger warning for my trigger warning and encourage you to not let my warning make you more sensitive than you already would be.”

Then, about a year ago, I had an epiphany. [I feel compelled to warn you that my epiphany might just be common sense, but it felt epiphany-like to me]

I realized—perhaps aided by my experiences training to do hypnosis—that trigger warnings might be functioning as negative suggestions, implying that people might not be able to handle the content and priming them to notice and focus on their negative reactions.

Given my epiphany, I was energized—as the solution-focused people like to say—to do something different. The different thing I settled on was to invent “The Strength Warning.”

[Here’s where I digress again to pitch a podcast. Paula Fontenelle, an all-around wonderful, kind, and competent professional, has a new podcast called, Relating to AI. And, lucky me, I got to be one of her very first guests. And, lucky Paula (joking now), she got to have me start her podcast interview by explaining and demonstrating the strength warning. Consequently, if you’re interested in AI and/or in hearing me demonstrate the strength warning, the link to Paula’s podcast is here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MHDIYrXw_2Y]

Although watching/listening to me give the strength warning with Paula is way more fun, I will also describe it below.

For strengths warnings, I say things like this.

In addition to warning you about sensitive content coming up, I also want to give you a Strength Warning. A strength warning is mostly the opposite of a trigger warning. I want you to watch out for the possibility that being here together in this lecture and with your colleagues might just make you notice yourself feeling stronger, feeling better, feeling more prepared, feeling more knowledgeable, and maybe even feeling smarter. So . . . watch for that, because I think you might even be stronger than you think you are.

Please, let me know what you think about my invention of the strength warning. I encourage you to try it out when you’re teaching or presenting.

I also encourage you to try out Paula’s new podcast. If you do, you might feel smarter, stronger, and more prepared to face the complicated issue of having AI intrude on our lives.

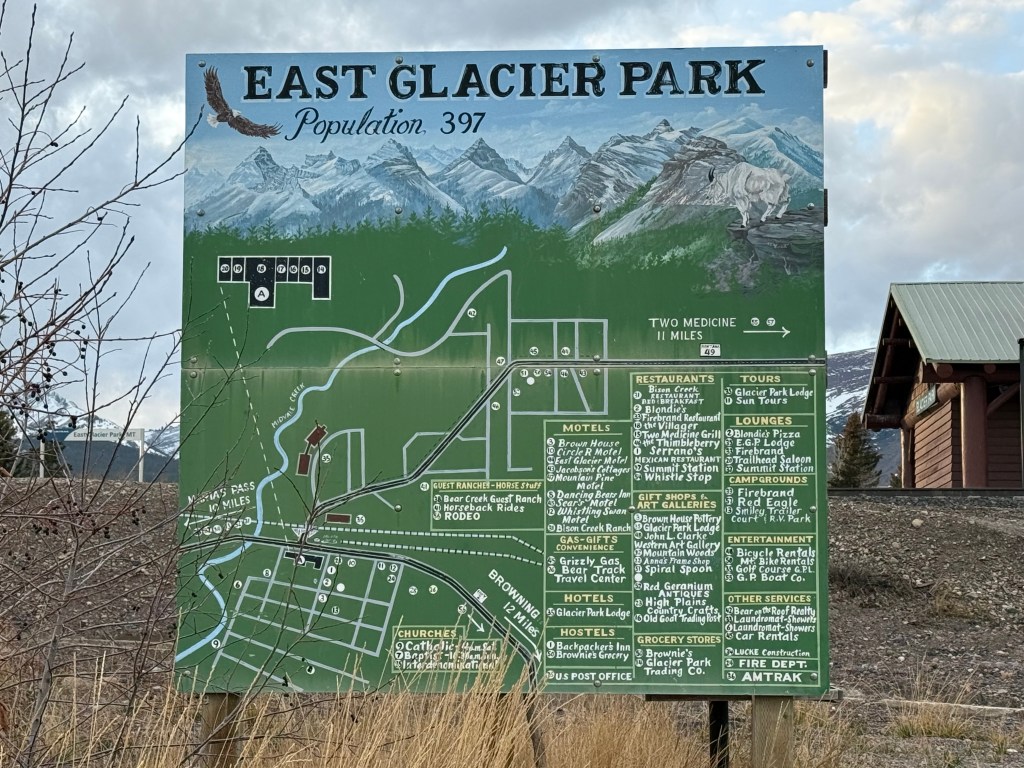

Strengths-Based Suicide Prevention on the Blackfeet Reservation

Today, Tammy Tolleson Knee and completed day 1 of a 2-day course on Strengths-Based Suicide Assessment and Interventions in Schools at the Buffalo Hide Academy of Browning Public Schools on the Blackfeet Reservation. We are beyond happy for this opportunity. It’s the first time for Tammy and I to present together (for two days!). As frosting on the presentation cake, Rita is here with us, watching, listening, heckling, and guiding.

In case you haven’t heard, Browning Public Schools and their staff have already started integrating strengths-based suicide prevention work into their programming. Two of our former University of Montana school counseling graduates, Sienna and Charlie Speicher are at the center of this work. Sienna and Charlie have already taught strengths-based courses through Blackfeet Community College, and they founded the Firekeeper Alliance. Here’s the Firekeeper Alliance Mission Statement:

Our mission is to cultivate resources, attention, and awareness to ultimately transform perspectives regarding suicidal distress in Indian Country and to help reduce suicide rates in our communities. We believe that mainstream and current approaches of suicide assessment and intervention struggle to meet the unique needs of Tribal populations. The Firekeeper Alliance promotes a different set of strengths-based, decolonized ideals around suicidal behavior. We believe that systemic and cultural shifts in the clinical community are necessary to truly make a positive change.

The Firekeeper Alliance also focuses on several areas, including offering strengths-based approaches to counseling, as in the following:

- Offer individual and group counseling sessions utilizing evidence-based therapies which are effective in addressing suicidality.

- Promote assessment techniques and interventions that elicit protective factors and a resilient spirit.

- Administer assessment instruments that screen for strengths, character assets, and benevolent experience to depathologize suicidal distress.

- Advocate for strengths based assessment and intervention approaches to be used in conjunction with cultural healing mechanisms.

Back to our training. . .here are the ppts that Tammy and I developed. There are SO MANY, but then again, we’re covering two whole days!

In closing, I want to give a big shout-out to Browning Public Schools (BPS) for collaborating with us (the Center for the Advancement of Positive Education; aka CAPE) to bring this training to Browning. Not only do we have a dozen or so school counselors in the room, we’ve also got a dozen or so administrative staff, including principals and the BPS superintendent. We had a blast today and are looking forward to more meaningful fun tomorrow!

John SF

Slides for the ACA Practice Summit TODAY!

Hi All,

Here are my slides for today. I hope you all have a fantastic Friday.

The Montana Healthcare Foundation Summit in Bozeman — Slide decks

I’m looking forward to a morning drive to Bozeman where I’ll meet and talk with healthcare and mental health providers and advocates from all around Montana. In advance of the Summit, I want to say thank you to the Montana Healthcare Foundation and to all the participants for their dedication to the well-being of all Montanans.

I have two talks . . . and the slide decks are linked below:

Who Are You? A Request

We’re in the throes of editing our Theories text, meaning I’m so deep into existential, feminist, and third wave counseling and psychotherapy theories that I may have lost myself. If any of you find me somewhere on the street babbling about Judith Jordan and Frantz Fanon and Bryan Cochran, please guide me home.

This brings me to a big ask.

As part of 4th wave feminism, we’re more deeply integrating intersectionality into the practice of feminist therapy. Among other things, intersectionality is about identity. I’m interested in using a variation of Irvin Yalom’s “Who are you?” group technique to explore identity in anyone willing to respond to this post.

To participate, follow these instructions.

- Clear a space for thinking, writing, and exploring your identity.

- Ask yourself the question: “Who am I?” and write down the response as it flows into your brain/psyche.

- Repeat this process nine more times, for a total of 10 responses, numbering each response. One rule about this: You can’t use the same response twice.

- After you finish your list of 10, write a paragraph or two about how you were affected by this activity.

- If you’re comfortable sharing, send me your list of 10 identities along with your reflections (email: john.sf@mso.umt.edu). If you prefer the more public route, you can post your responses here on my blog. Either way, because I’m in 24/7 theories mode, you may not hear back from me until middle November!

There’s a chance I might want to quote one or more of you in the theories text, instructor’s manual, student guide, or in this blog. If that’s the case, I will email you and request permission.

Thanks for considering this activity and request. Identity and identity development are fascinating. Whether we’re talking about multiple identities (intersectionality), emotions and behaviors (Blake), or the “microbes within us” (Yong), we all contain multitudes.