Everybody loves a good story.

Good stories grab the listener’s attention and don’t let go. I’ve been reading and telling stories for as long as I can remember. Whether its kindergartners, clients, or college students, I’ve found that stories settle people into a receptive state that looks something like a hypnotic trance.

Nowadays, mostly we see children and teens entranced with their electronic devices, television, and movies. Although it’s nice to see young people in a calm and focused state, the big problem with devices (other than their negative effects on sleep, attention span, weight, brain development, and nearly everything else having to do with living in the real world), is that we (parents, caretakers, and concerned adults), don’t have control over the electronic stories our children see and hear.

Storytelling is a natural method for teaching and learning. Children learn from stories. We’re teaching when we tell them. We might as well add our intentional selection of stories to whatever our children might be learning from the internet.

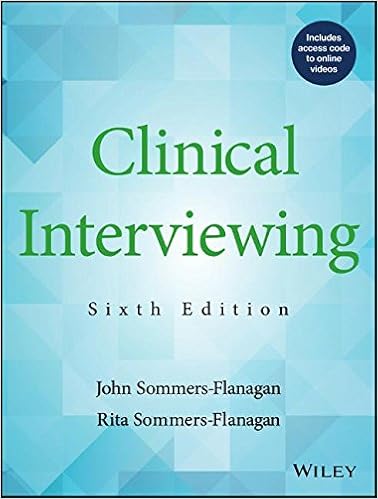

Way back in 1997, Rita and I wrote a book called Tough Kids, Cool Counseling. One of the chapters focused on how to use therapeutic storytelling with children and teens. Although the content of Tough Kids, Cool Counseling is dated, the ideas are still solid. The following section is good material for counselors, psychotherapists, parents, and other adults who want to influence young people.

In counseling, storytelling was originally developed as a method for bypassing client resistance. Stories are gentle methods that don’t demand a response, but that stimulate, “thinking, experiencing, and ideas for problem resolution” (Lankton & Lankton, 1989, pp. 1–2)

Storytelling is an alternative communication strategy. For counselors, it should be used as a technique within the context of an overall treatment plan, rather than as a treatment approach in and of itself. For parents and caregivers, stories should be fun, and engaging . . . and told in ways that facilitate learning.

Story construction. Even if you’re an excellent natural storyteller, it can help to have a guide or structure for story construction and development. I like using a framework that Bill Cook, a Montana psychologist, wrote about and shared with me. He uses the acronym S-T-O-R-I, to organize the parts of a therapeutic story.

S: Set the stage for the story. To set the stage, you should create a scenario that focuses on a child living in a particular situation. The child can be a human or an animal or an animated object. The central child character should be described in a way that’s positive and appealing. Because much of my work back in the 1990s involved working with boys who were angry and impulsive, the following story features a boy who has an arguing problem. Depending on your circumstances, you could easily feature a girl or a child who doesn’t have a particular gender identity.

Here’s the beginning of the story.

Once upon a time there was a really smart boy. His name was Lancaster. Lancaster was not only smart, he was also a very cool dresser. He wore excellent clothes and most everyone who met Lancaster immediately was impressed with him. Lancaster lived with his mother and sister in the city.

In this example, the client’s name was Larry. If it’s not too obvious, you can give the central character a name that sounds similar to your client’s name. You may also develop a story that has other similarities to your client’s life.

T: Tell about the problem. This stage includes a problem with which the central character is struggling. It should be a problem similar to your client’s or your child’s. This stage ends with a statement about how no one knows what to do about this very difficult and perplexing problem.

Every day, Lancaster went to school. He went because he was supposed to, not because he liked school. You see, Lancaster didn’t like having people tell him what to do. He liked to be in charge. He liked to be the boss. The bad news is that his teachers at school liked to be in charge too. And when he was at home, his mother liked to be the boss. So Lancaster ended up getting into lots of arguments with his teachers and mother. His teachers were very tired of him and about to kick him out of school. To make things even worse, his mother was so mad at him for arguing all the time that she was just about to kick him out of the house. Nobody knew what to do. Lancaster was arguing with everyone and everyone was mad at Lancaster. This was a very big problem.

O: Organize a search for helpful resources. During this part of the story, the central character and family try to find help to solve the problem. This search usually results in identifying a wise old person or animal or alien creature as a special helper. The wise helper lives somewhere remote and has a kind, gentle, and mysterious quality. In this case, because Larry (the client) didn’t have many positive male role models in his life, I chose to make the wise helper a male. Obviously, you can control that part of the story to meet the child’s needs and situation.

Because the situation kept getting worse and worse and worse, almost everyone had decided that Lancaster needed help—except Lancaster. Finally, Lancaster’s principal called Lancaster’s mom and told her of a wise old man who lived in the forest. The man’s name was Cedric and, apparently, in the past, he had been helpful to many young children and their families. When Lancaster’s mother told him of Cedric, Lancaster refused to see Cedric. Lancaster laughed and sneered and said: “The principal is a Cheese-Dog. He doesn’t know the difference between his nose and a meteorite. If he thinks it’s a good idea, I’m not doing it!”

But eventually Lancaster got tired of all the arguing and he told his mom “If you buy me my favorite ice cream sundae every day for a week, I’ll go see that old Seed-Head man. Lancaster’s mom pulled out her purse and asked, “What flavor would you like today?”

After hiking 2 hours through the forest, they arrived at Cedric’s tree house late Saturday morning. They climbed the steps and knocked. A voice yelled: “Get in here now, or the waffles will get cold!” Lancaster and his mom stepped into the tree house and were immediately hit with a delicious smell. Cedric waved to them like old friends, had them sit at the kitchen table, a served them a stack of toasty-hot strawberry waffles, complete with whipped cream and fresh maple syrup. They ate and talked about mysteries of the forest. Finally, Cedric leaned back, and asked, “Now what do you two want . . . other than my strawberry waffles and this pleasant conversation?”

Lancaster suddenly felt shy. His mom, being a sensitive mom, looked up at Cedric’s big hulking face and described how Lancaster could argue with just about anyone, anytime, anywhere. She described his tendency to call people mean names and mentioned that Lancaster was in danger of being kicked out of school. Of course, Lancaster occasionally burst out with: “No way!” and “I never said that,” and even an occasional, “You’re stupider than my pet toad.”

After Lancaster’s mom stopped talking, Cedric looked at Lancaster. He grinned and chuckled. Lancaster didn’t like it when people laughed at him, so he asked, “What are YOU laughing about?” Cedric replied, “I like that line. You’re even stupider than my pet toad. You’re funny. I’m gonna try that one out. How about if we make a deal? Both you and I will say nothing but “You’re even stupider than my pet toad” in response to everything anyone says to us. It’ll be great. We’ll have the most fun this week ever. Okay. Okay. Make me a deal.” Cedric reached out his hand.

Lancaster was confused. He just automatically reached back and said, “Uh, sure.”

Cedric quickly stood up and motioned Lancaster and his mom to the door, smiling and saying, “Hey you two toad-brains, see you next Saturday!!”

Searching for helpful resources can be framed in many ways. For counselors, you might construct it to be similar to what children and parents experience during their search for a counselor. Consistent with the classic Mrs. Piggle Wiggle book series, the therapeutic helper in the story has tremendous advantages over ordinary counselors. In the Lancaster example, Cedric gets to propose a maladaptive and paradoxical strategy without risk, because the whole process is simply a thought experiment. Depending on your preference and situation, you can use whatever “treatment” strategy you like.

R: Refine the therapeutic intervention. In this storytelling model, the initial therapeutic strategy isn’t supposed to be effective. Instead, the bad strategy that Cedric proposes is designed for a core learning experience. During the fourth stage (refinement) the central character learns an important lesson and begins the behavior change process.

Both Lancaster and Cedric had a long week. They called everyone they saw a “stupid toad-brain” and said, “You’re even stupider than my pet toad” and the results were bad. Lancaster got kicked out of school. That morning, when they were on their way to Cedric’s, Lancaster got slugged in the mouth for insulting their taxi driver and he was sporting a fat lip.

When Lancaster stepped into Cedric’s tree house, he noticed that Cedric had a black eye.

“Hey, Mr. Toad-Brain, what happened to your eye?” asked Lancaster. “Probably the same thing that happened to your face, fish lips!” replied Cedric.

Lancaster and Cedric sat staring at each other in awkward silence. Lancaster’s mom decided to just sit quietly to see what would happen. She felt surprisingly entertained.

Cedric broke the silence. “Here’s what I think. I don’t think everyone appreciates our humor. In fact, nobody I met liked the idea of having their brain compared to your pet toad’s brain. They never even laughed once. Everybody got mad at me. Is that what things are usually like for you?”

Lancaster muttered back, “Uh, well, yeah.” But this week was worse. My best friend said he doesn’t want to be best friends and my principal got so mad at me that he put my head in the toilet of the boys’ bathroom and flushed it.”

Cedric rolled his eyes and laughed, “And I thought I had a bad week. Well, Lanny, mind if I call you Lanny?”

“Yeah, whatever, Just don’t call me anything that has to do with toads.”

“Well Lanny, the way I see it, we have three choices. First, we can keep on with the arguing and insulting. Maybe if we argue even harder and used different insults, people will back down and let us have things our way. Second, we can work on being really nice to everyone most of the time, so they’ll forgive us more quickly when we argue with them in our usual mean and nasty way. And third, we can learn to argue more politely, so we don’t get everyone upset by calling them things like ‘toad brains’ and stuff like that.”

After talking their options over with each other and with Lancaster’s mom, Cedric and Lancaster decided to try the third option: arguing more politely. In fact, they practiced with each other for an hour or so and then agreed to meet again the next week to check on how their new strategy worked. Their practice included inventing complimentary names for each other like “Sweetums” or “Tulip” and surprising people with positive responses like, “You’re right!” or “Yes boss, I’m on it!”

As seen in the narrative, Lanny and Cedric learn lessons together. The fact that they learn them together is improbable in real life. However, the storytelling modality allows counselor and client the opportunity to truly form a partnership and enact Aaron Beck’s concept of collaborative empiricism.

I: Integrating the lesson. In the final stage of this storytelling model, the central character articulates the lesson(s) learned.

Months later, Lancaster got an invitation from Cedric for an ice cream party. When Lancaster arrived, he realized the party was just for him and Cedric. Cedric held up his glass of chocolate milk and offered a toast. He said, “To my friend Lanny. I could tell when I first met you that you were very smart. Now, I know that you’re not only smart, but you are indeed wise. Now, you’re able to argue politely and you only choose to argue when you really feel strongly about something. You’re also as creative in calling people nice names as you were at calling them nasty names. And you’re back in school and, as far as I understand, your life is going great. Thanks for teaching me a memorable lesson.”

As Lanny raised his glass for the toast, he noticed how strong and good he felt. He had learned when to argue and when not to argue. But even more importantly, he had learned how to say nice things to people and how to argue without making everyone mad at him. The funny thing was, Lanny felt happier. Mostly, all those mad feelings that had been inside him weren’t there anymore.

At the end of this story (or whatever story you decide to use), you can directly discuss the “moral of the story” or just leave it hanging. In many cases, leaving the story’s message unstated is useful. Alternatively, you might ask the child, “What do you think of this story?”

Letting the child consider the message provides an opportunity for intellectual stimulation and may aid in moral development. Although it would be nice to claim that therapeutic storytelling causes immediate behavior change, the more important outcome is that storytelling provides a way for an adult and a child to have pleasant interactions around a story . . . with the possibility that, over time, positive behavior change may occur.