Every day, I keep getting older. I can’t seem to stop myself. And every day, I keep running into dialectics. They’re everywhere. My aging experiences of ubiquitous dialectics seems consistent with the fact that yesterday, Merriam-Webster declared “polarization” their word of the year (https://www.merriam-webster.com/wordplay/word-of-the-year).

Boo, Merriam-Webster! I would have chosen dialectics. Here’s one of the definitions for dialectic listed in the online M-W dictionary: “the Hegelian process of change in which a concept or its realization passes over into and is preserved and fulfilled by its opposite.” TBH, I have very little understanding of what the heck Hegel was talking about, but I’m pretty sure it’s happening ALL. THE. TIME.

This morning I find myself plagued by the idea that although most mental health professionals advocate mindfulness, many mental health professionals (including myself, sometimes), aren’t very mindful when using basic counseling skills in practice. Today’s topic is questions. I’m polarized inside a dialectical and thinking, “We should all be more mindful and intentional in our use of questions in counseling and psychotherapy.” At the same time, I’m sure, “we should all relax and be more of ourselves.”

With these confusing caveats in mind, today, tomorrow, and maybe the next day, I’m posting about the very basic use of questions in counseling and psychotherapy. This content is excerpted from our Clinical Interviewing textbook.

Here’s our opening section on questions, which is conveniently found in Chapter 5 of Clinical Interviewing, which I’m continually surprised that not everyone has read (but really not at all surprised).

**************************************

Questions

Imagine digging a hole without a shovel or building a house without a hammer. For many clinicians, conducting an interview without using questions constitutes an analogous problem: How can you complete the interviewing task without using your most basic tool?

Despite the central role of questions in clinical interviewing, we’ve avoided discussing them until now. Similarly, when teaching clinical interviewing skills, we usually prohibit question asking for a significant portion of the course (J. Sommers-Flanagan & Means, 1987). Our rationale includes several factors: Questions are easy and often misused. Also, because questioning isn’t the same thing as listening, our goal is for students to develop alternative information-gathering strategies. Asking questions can get in the way of gathering important information from clients. The Little Prince expresses a fundamental problem with excessive questioning.

Grown-ups love figures. When you tell them that you have made a new friend, they never ask you any questions about essential matters. They never say to you, “What does his voice sound like? What games does he love best? Does he collect butterflies?” Instead, they demand: “How old is he? How many brothers has he? How much does he weigh? How much money does his father make?” Only from these figures do they think they have learned anything about him. (de Saint-Exupéry, 1943/1971, p. 17)

The questions you ask may be of no value to the person being asked. Ideally, your questions should focus on what seems most important to clients.

Despite our reservations about excessive questioning, questions are a diverse and flexible interviewing tool; they can be used to

- Stimulate client talk

- Inhibit client talk

- Facilitate rapport

- Show interest in clients

- Show disinterest in clients

- Gather information

- Confront clients

- Focus on solutions

- Ignore the client’s viewpoint

- Stimulate insight

There are many forms or types of questions. Differentiating among them is important, because different question types produce different client responses. In this section, we describe open, closed, swing, indirect, and projective questions. Chapter 6 covers therapeutic questions. Although we distinguish between general question types and therapeutic questions, all questioning can be used for assessment or therapeutic purposes.

Open Questions

Open questions are used to facilitate talk; they pull for more than a single-word response. Open questions ordinarily begin with either How or What. Sometimes questions that begin with Where, When, Why, and/or Who are classified as open, but such questions are only partially open because they don’t facilitate talk as well as How and What questions (Cormier, Nurius, & Osborn, 2017). The following hypothetical dialogue illustrates how using open questions may or may not stimulate client talk:

Therapist: When did you first begin having panic attacks?

Client: In 1996.

Therapist: Where were you when you had your first panic attack?

Client: I was just getting on the subway in New York City.

Therapist: What happened?

Client: When I stepped on the train, my heart began to pound. I thought I was dying. I just held on to the metal post next to my seat because I was afraid I would fall over and be humiliated. I felt dizzy and nauseated. I’ve never been back on the subway again.

Therapist: Who was with you?

Client: No one.

Therapist: Why haven’t you tried to ride the subway again?

Client: Because I’m afraid I’ll have another panic attack.

Therapist: How are you handling the fact that your fear of panic attacks is so restrictive?

Client: Not so good. I’ve been getting more and more scared to go out. I’m afraid that soon I’ll be too scared to leave my house.

As you can see from this example, open questions vary in their openness. They don’t uniformly facilitate depth and breadth of talk. Although questions beginning with What or How usually elicit the most elaborate responses from clients, that’s not always the case. More often, what’s important is the way a particular What or How question is phrased. For example, “What time did you get home?” and “How are you feeling?” can be answered very succinctly. The openness of a particular question should be judged primarily by the response it usually elicits.

Questions beginning with Why are unique in that they commonly elicit defensive explanations. Meier and Davis (2020) wrote, “Questions, particularly ‘why’ questions, put clients on the defensive and ask them to explain their behavior” (p. 23). Why questions frequently produce one of two responses. First, as in the preceding example, clients may respond with a form of “Because!” and then explain, sometimes through detailed and intellectual responses, why they’re thinking or acting or feeling in a particular manner. Second, some clients defend themselves with a “Why not?” response. Or, because they feel attacked, they respond confrontationally with “Is there anything wrong with that?” Therapists minimize Why questions because they exacerbate defensiveness and intellectualization and diminish rapport. In contrast, if rapport is good and you want your client to move away from emotions and speculate or intellectualize about something, then a Why question may be appropriate and useful.

Closed Questions

Closed questions usually begin with words such as Do, Does, Did, Is, Was, or Are and can be answered with a yes or no response. They’re useful if you want to solicit specific information. Traditionally, closed questions are used later in the interview, when rapport is established, time is short, and efficient questions and short responses are needed (Morrison, 2007). Questions that begin with Who, Where, or When also tend to direct clients toward talking about specific information; therefore, they should be considered closed questions (see Practice and Reflection 5.1).

Closed questions restrict verbalization and lead clients toward details. They can reduce or control how much clients talk. Restricting verbal output is useful when working with clients who talk excessively. Closed questions are used to clarify behaviors and symptoms and consequently used when conducting diagnostic interviews. (For example, in the preceding example about a panic attack on the New York subway, a diagnostic interviewer might ask, “Did you feel lightheaded or dizzy?” This question would help confirm or disconfirm one symptom possibly linked to panic disorder.). As compared to open questions, closed questions usually feel different to clients.

Sometimes, therapists inadvertently or intentionally transform open questions into closed questions with what’s called a tag query. For example, you might start with, “What was it like for you to confront your father after all these years,” and then tag “was it gratifying?” onto the end.

Transforming open questions into closed questions is fine if you want to limit client elaboration. When asked closed question, clients will likely focus solely on the answer (e.g., whether they felt gratification when confronting their father, as in the preceding example). Clients may or may not elaborate on feelings of fear, relief, resentment, or other thoughts, emotions, and sensations.

If you begin an interview using a nondirective approach, but later change styles to obtain more specific information through closed questions, it’s wise to use role induction to inform your client of your forthcoming shift. You might say,

We have about 15 minutes left, and I have a few things I want to make sure I’ve covered, so I’m going to start asking you more specific questions.

Beginning therapists are usually advised to avoid closed questions because closed questions are frequently interpreted as veiled suggestions. For example:

Client: Ever since my husband came back from active duty, he’s been moody, irritable, and withdrawn. This makes me miss him terribly, even though he’s home. I just want my old husband back.

Therapist: Have you tried telling him how you’re feeling?

We usually boldly tell our students to never ask, “Have you tried. . .” We believe have you questions are advice-giving in disguise. We’re not against advice; we’re just against asking questions that imply clients should have already tried what you’re recommending. In the preceding interaction, the client might think the therapist is suggesting she should open up to her husband about her feelings. Although this may be a reasonable idea, therapists and clients are better served with an open question: “What have you tried to help get your old husband back?” Our advice—which is not disguised in the least—is that when you feel an impulse to ask a “have you” question (and you will), simply stop yourself, and add the word “What” to the beginning to make it an open question. Closed questions are a helpful interviewing tool—as long as they’re used intentionally and in ways consistent with their purpose.

Swing Questions

Swing questions can function as either closed or open questions; they can be answered with yes or no, but they also invite more elaborate discussion of feelings, thoughts, or issues (Shea, 1998). Swing questions usually begin with Could, Would, Can, or Will. For example:

- Could you talk about how it was when you first discovered you were pregnant?

- Would you describe how you think your parents might react to finding out you’re leaving?

- Can you tell me more about that?

- Will you tell me what happened in the argument between you and your daughter last night?

Ivey and colleagues (2023) believe swing questions are the most open of all questions. They note that clients are empowered to decline answering a swing question by saying something like, “No. I’d rather not talk about that.”

For swing questions to work, you should observe two basic rules. First, avoid using swing questions unless rapport has been established. Without rapport, swing questions may backfire and function as a closed question (i.e., the client responds with a shy or resistant yes or no). Second, avoid using swing questions with children and adolescents, especially early in the relationship. This is because children and adolescents often interpret swing questions concretely and respond accordingly (J. Sommers-Flanagan & Sommers-Flanagan, 2007b). For example:

Counselor 1: Would you tell me more about the fights you’ve been having with your classmates?

Young Client 1: No.

Counselor 2: Could you tell me about how you felt when your dad left?

Young Client 2: No.

Counselor 3: Would you like to come back to my office?

Young Client 3: No.

Swing questions with young clients (especially if you don’t have positive rapport) can produce awkward and unhelpful interactions.

Indirect or Implied Questions

Indirect or implied questions usually begin with I wonder or You must or It must (Benjamin, 1987). They’re used when therapists don’t want to directly ask or pressure clients to respond. The following are examples of indirect or implied questions:

- I wonder how you’re feeling about your upcoming wedding.

- I’m wondering about your plans after graduation.

- I’m curious if you’ve given any thought to searching for a job.

- You must have some thoughts or feelings about discovering your child is transgender.

- It must be hard for you to cope with your wife being shipped out to serve overseas.

You can use other indirect sentence stems to gently imply a question or prompt clients to speak about a topic. Common examples include “I’d like to hear about…” and “Tell me about…”

Indirect or implied questions can be useful early in interviews or when approaching delicate topics. Like immediacy, they can contain a supportive self-disclosure of interest. They’re noncoercive, so they may be especially useful as an alternative to direct questions with clients who seem reticent (C. Luke, personal communication, August 7, 2012). When overused, indirect questions can seem sneaky or manipulative; after repeated “I wonder…” and “You must…” probes, clients may start thinking, “And I’m wondering why you don’t just ask me whatever it is you want know!”

Projective or Presuppositional Questions

Projective questions are used to ask clients to imagine particular scenarios and help them identify, explore, and clarify unconscious or unarticulated conflicts, values, thoughts, and feelings (see Case Example 5.5). Solution-focused therapists refer to projective questions as presuppositional questions (Murphy, 2023). These questions typically begin with some form of What if and invite client speculation. Projective questions can trigger mental imagery and prompt clients to explore thoughts, feelings, and behaviors they might have if they were in a particular situation. For example:

- What would you do if you were given one million dollars?

- If you had three wishes, what would you wish for?

- If you needed help or were really frightened, or even if you were just totally out of money and needed some, who would you turn to right now? (J. Sommers-Flanagan & Sommers-Flanagan, 1998, p. 193)

- What if you could go back and change how you acted during that argument (or other significant life event): What would you do differently?

Projective questions are also used to evaluate client values, decision making, and judgment. For example, a therapist can analyze a response to the question “What would you do with one million dollars?” to glimpse client values and self-control. Projective questions are sometimes included as a part of mental status examinations (see Chapter 9 and the Appendix).

CASE EXAMPLE 5.5: PROJECTIVE QUESTIONING TO ELICIT VALUES

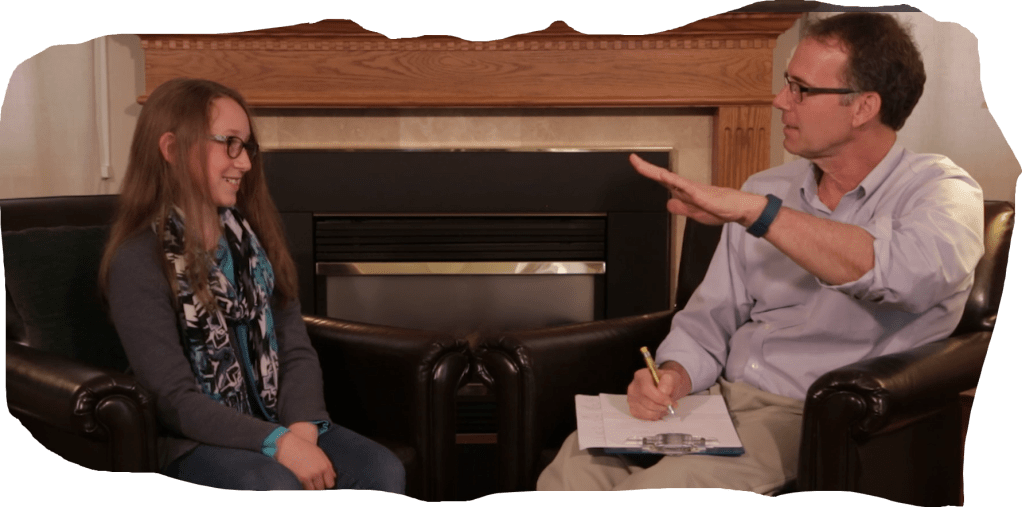

Your use of projective questions is limited only by your creativity. John likes to use projective questions to explore relationship dynamics and values. For example, with a 15-year-old male client who had an estranged relationship with his father and was struggling in school, John asked, “If you did really well on a test, who’s the first person you would tell?” The client responded, “My dad.” After hearing this response, John used the fact that the boy continued to value his father’s approval to encourage the boy and his father to meet together for counseling to improve their communication and relationship.

[End of Case Example 5.5]

And . . . here’s a pdf of the Chapter 5 Table describing the different question types.