A friend and colleague in the Counseling Department at the University of Montana forwarded me an article by Lucy Foulkes of Oxford University titled, “Mental-health lessons in schools sound like a great idea. The trouble is, they don’t work.”

That is troubling. My friend knows I’ve been thinking about these things for years . . . and I feel troubled about it too.

Children’s behavioral or mental or emotional health has been in decline for decades. COVID made things worse. Even at the University, our collective impression is that current students—most of whom are simply fantastic—are more emotionally fragile than we’ve ever seen before.

As Craig Bryan says in his remarkable book, “Rethinking Suicide,” big societal problems like suicide, homelessness, addiction, and mental health are “wicked problems” that often respond to well-intended efforts by not responding, or by getting worse.

Such is the case that Lisa Foulkes is describing in her article.

I’ve had a front row seat to mental health problems getting worse for about 42 years now. Oh my. That’s saying something. Mostly it’s saying something about my age. But other than my frightening age, my point is that in my 42+ years as a mental health professional, virtually everything in the mental health domain has gotten worse. And when I say virtually, I mean literally.

Anxiety is worse. Depression is worse. ADHD is worse, not to mention bipolar, autism spectrum disorder, suicide, and spectacular rises in trauma. I often wonder, given that we have more evidence-based treatments than ever before in the history of time . . . and we have more evidence-based mental health prevention programming than ever before in the history of time . . . how could everything mental health just keep on going backward? The math doesn’t work.

In her article, Lisa Foulkes points out that mental health prevention in schools doesn’t work. To me, this comes as no big surprise. About 10 years ago, mental health literacy in schools became a big deal. I remember feeling weird about mental health literacy, partly because across my four decades as an educator, I discovered early on that if I presented the diagnostic criteria for ADHD to a class of graduate students, about 80% of them would walk away thinking they had ADHD. That’s just the way mental health literacy works. It’s like medical student’s disease; the more you learn about what might be wrong with you the more aware and focused you become on what’s wrong with you. We’ve known this since at least the 1800s.

But okay, let’s teach kids about mental health disorders anyway. Actually, we’re sort of trapped into doing this, because if we don’t, everything they learn will be from TikTok. . . which will likely generate even worse outcomes.

I’m also nervous about mindful body scans (which Foulkes mentions), because they nearly always backfire as well. As people scan their bodies what do they notice? One thing they don’t notice is all the stuff that’s working perfectly. Instead, their brains immediately begin scrutinizing what might be wrong, lingering on a little gallop in their heart rhythm or a little shortness of breath or a little something that itches.

Not only does mental health education/prevention not work in schools, neither does depression screenings or suicide screenings. Anyone who tells you that any of these programs produces large and positive effects is either selling you something, lying, or poorly informed. Even when or if mental health interventions work, they work in small and modest ways. Sadly, we all go to bed at night and wake up in the morning with the same brain. How could we expect large, dramatic, and transformative positive outcomes?

At this point you—along with my wife and my team at the Center for the Advancement of Positive Education—may be thinking I’ve become a negative-Norman curmudgeon who scrutinizes and complains about everything. Could be. But on my good days, I think of myself as a relatively objective scientist who’s unwilling to believe in any “secret” or public approaches that produce remarkably positive results. This is disappointing for a guy who once hoped to develop psychic powers and skills for miraculously curing everyone from whatever ailed them. My old college roommate fed my “healer” delusions when, after being diagnosed with MS, “I think you’ll find the cure.”

The painful reality was and is that I found nothing helpful about MS, and although I truly believe I’ve helped many individuals with their mental health problems, I’ve discovered nothing that could or would change the negative trajectory of physical or mental health problems in America. These days, I cringe when anyone calls themselves a healer. [Okay. That’s likely TMI.]

All this may sound ironic coming from a clinical psychologist and counselor educator who consistently promotes strategies for happiness and well-being. After what I’ve written above, who am I to recommend anything? I ask that question with full awareness of what comes next in this blog. Who am I to offer guidance and educational opportunities? You decide. Here we go!

*********************************************

The Center for the Advancement of Positive Education (CAPE) and the Montana Happiness Project (that means me and my team) are delighted to be a part of the upcoming Jeremy Bullock Safe Schools Conference in Billings, MT. The main conference will be Aug 5-6. You can register for the conference here: https://jeremybullocksafeschools.com/register. The flyer with a QR code is here:

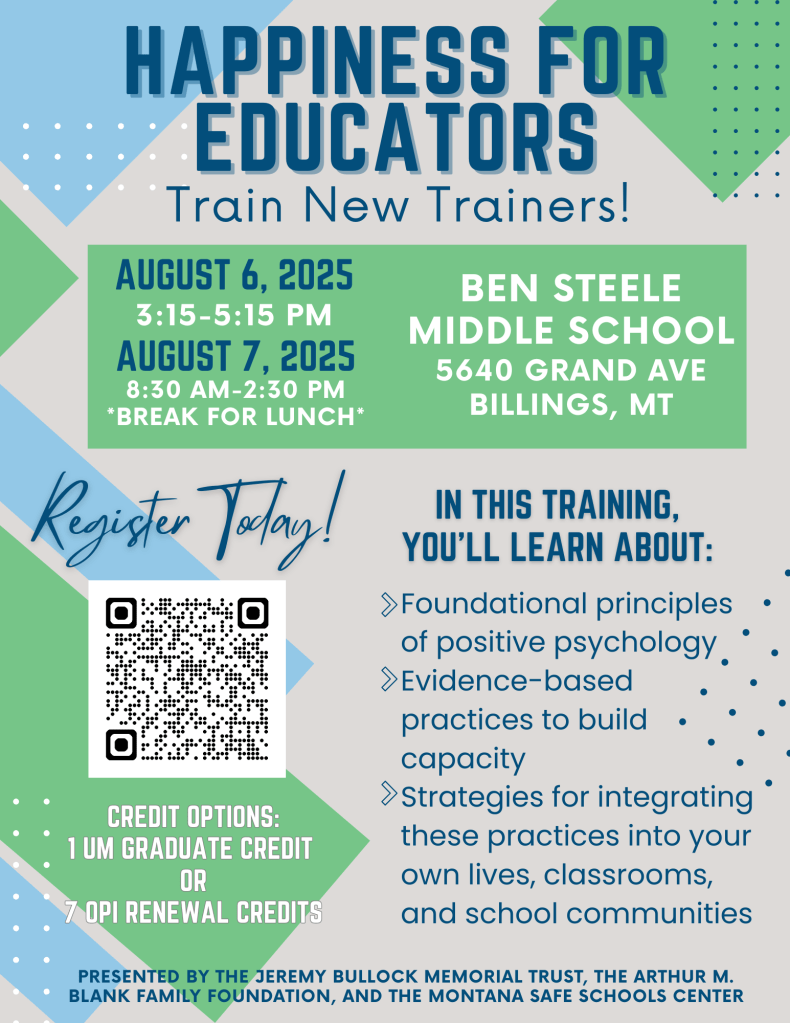

In the same location, beginning on the afternoon of Aug 6 and continuing for most of Aug 7, CAPE is offering a “Montana Happiness” infused 7-hour bonus training. Using our combined creative skills, we’ve decided to call our workshop: “Happiness for Educators.” Here’s the link to sign up for either a one-credit UM grad course (extra work is required) or 7 OPI units: https://www.campusce.net/umextended/course/course.aspx?C=763&pc=13&mc=&sc=

The flyer for our workshop, with our UM grad course or OPI QR code is at the top of this blog post.

In the final chapter of Rethinking Suicide, Craig Bryan, having reviewed and lamented our collective inability to prevent suicide, turns toward what he views as our most hopeful option: Helping people create lives worth living. Like me, Dr. Bryan has shifted from a traditional suicide prevention perspective to strategies for helping people live lives that are just a little more happy, meaningful, and that include healthy supportive relationships. IMHO, this positive direction provides hope.

In our Billings workshop, we’ll share, discuss, and experience evidence-based happiness strategies. We’ll do this together. We’ll do it together because, in the words of the late Christopher Peterson, “Other people matter. And we are all other people to everyone else.”

Come and join us in Billings . . . for the whole conference . . . or for our workshop . . . or for both.

I hope to see you there.