Last Friday night (or Saturday morning in South Korea), I had the honor and privilege of spending three hours online with 45 South Korean therapists. We were talking, of course, about strengths-based suicide assessment and treatment. Given my limited Korean language skills (is it accurate to say my language skills are limited if I can’t say or comprehend ANYTHING in Korean?), I had a translator. Although I couldn’t tell anything about the translation accuracy, my distinct impression was that she was absolutely amazing.

I had a friend ask how I happened to get invited to present to Korean therapists. My main response is that I believe the time is right (aka Zeitgeist) for greater integration of the strengths-based approach into traditional suicide assessment and treatment. The person who recruited me was Dr. Julia Park, another absolutely amazing, kind, and competent South Korean person, who also happens to hold an Adlerian theoretical orientation. Thanks Julia!

Just for fun, I wish I had my Korean translated ppts to share here. They’re unavailable, and so instead I’m sharing an excerpt from Chapter 10 (Suicide Assessment Interviewing) of our Clinical Interviewing (2024) textbook. The section I’m featuring is the part where we review issues and procedures around suicide risk categorization and decision-making.

You may already know that some of the latest thinking on suicide risk assessment is that we should not use instruments like the Columbia to categorize risk. You also may know that not only am I a believer in this latest thinking, I can be wildly critical of efforts to categorize suicide risk. . . so much so that I often end up using profanity in my professional presentations. Of course, because the context is a professional presentation, I only use the highly professional versions of profanity.

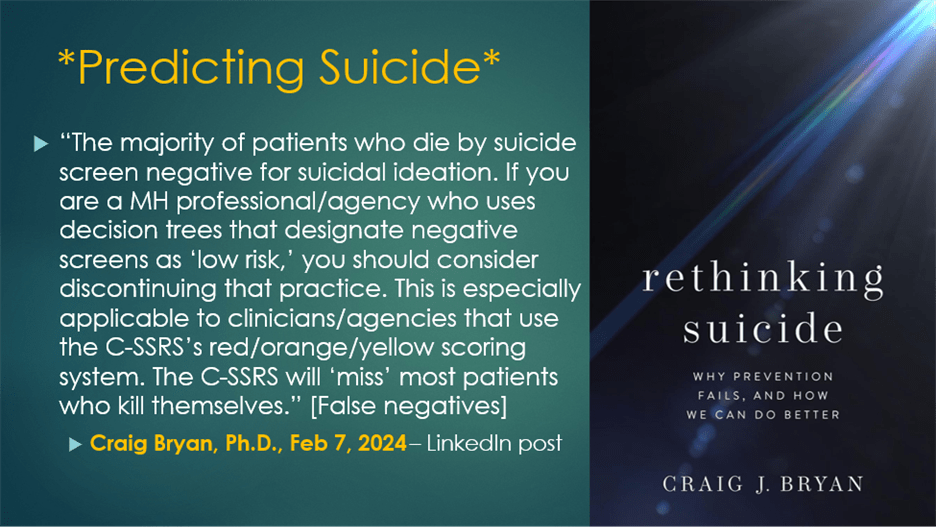

Here’s a LinkedIn comment about that issue from Craig Bryan. Dr. Bryan is a suicide researcher, professor at The Ohio State University, and author of “Rethinking Suicide.” In support of him and his research and thinking, I’d like to professionally say that although I lean away from reductionistic categorization of things, all signs point to the likelihood that Dr. Bryan has a very large brain.

The good news is that I feel validated by Dr. Bryan’s strong comments against categorizing suicide risk. But the bad news is that we all live in the real world and in the real world sometimes professionals have to do more than just swear about risk categorization—we have to actually make recommendations for or against hospitalization, consult with other professionals who want our opinion, and quoting me as saying that risk factor categorization is pure bullshit may not be the best and most professional option.

So . . . what are we to do? First, we parse Dr. Bryan’s comments. He’s not saying NEVER categorize risk or make risk estimates. He’s saying don’t categorize “negative screens as low risk” which is slightly different than don’t try to estimate risk. His message is that we have too many false negatives—where someone screens negative and then dies by suicide. In other words, we should not be confident and say negative screens are “low risk.” That’s different from throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

It might be easy to think that Dr. Bryan’s comments are discouraging. But I view him as just saying we should be careful professionals. To help with that, below is the excerpt on Suicide risk categorization and decision-making, from our textbook. If you’re in a situation where you have to make a professional recommendation about suicide risk, this information may be helpful. BTW, the reason I was inspired to post this excerpt is because the Korean participants were wonderful and asked lots of hard questions, including questions related to this topic.

Suicide Risk Categorization and Decision-Making

Throughout this chapter, we have acknowledged the limits of categorizing clients on the basis of risk. The current state of the science indicates that efforts to predict client suicides (i.e., categorize risk) are likely to fail. Nevertheless, when necessary—because of institutional requirements or client inability to collaborate on safety or treatment planning—all clinicians should be able to use their judgment to estimate risk and make disposition decisions for the welfare of the client. As a consequence, we review a suicide risk categorization and decision-making model next.

Consultation

Consultation with peers and supervisors serves a dual purpose. First, it provides professional support; dealing with suicidal clients is difficult and stressful; input from other professionals is helpful. For your health and sanity, you shouldn’t do work with suicidal clients in isolation.

Second, consultation provides feedback about appropriate practice standards. Should you need to defend your actions and choices following a suicide death, you’ll be able to show you were meeting professional standards. Consultation is one way to monitor, evaluate, and upgrade your professional competency.

Suicide Risk Assessment: An Overview

We reviewed an overwhelming number of suicide risk and protective factors earlier in this chapter. Generally, more risk factors equate to more risk. However, some risk factors are particularly salient. These include:

Previous attempts

A previous attempt is sometimes viewed as suicide rehearsal. Two previous attempts are especially predictive of suicide because they represent repeated intent. Also, when previous attempts were severe and the client was disappointed not to die, risk is high.

Command hallucinations

When clients are experiencing a psychotic state accompanied by command hallucinations (e.g., a voice that says, “You must die’), risk is at an emergency level.

Severe depression with extreme agitation

The combination of depression and agitation can be especially lethal. Agitation can take the form of extreme anxiety or extreme anger.

Protective factors

A single protective factor may outweigh many risk factors. But, it’s impossible to know the power of any individual protective factors without an in-depth discussion with your client. Engagement in therapy and collaboration on a safety plan (and the hope these behaviors signal) can substantially reduce risk.

Nature of Suicidal ideation

As discussed earlier, suicidal ideation is evaluated based on frequency, triggers, intensity, duration, and termination. Some clients live chronically with high suicidal ideation frequency, intensity, and duration—and are low risk. However, if ideation is frequent and intense and accompanied by intent and planning, risk is high.

Suicide Intent

Suicide intent is the factor most likely to move clients toward lethal attempts. Intent can be based on objective or subjective signs. Objective signs of intent include one (or more) previous lethal attempt(s). Subjective signs of intent can include a client rating of intent or client report of a highly lethal plan.

Clinical Presentation

How clients present themselves during sessions is revealing. Clients can be palpably hopeless, talk desperately about feelings of being trapped, and express painful and unremitting self-hatred or shame. But if clients have adapted to these experiences, they may not have accompanying intent and active planning. Observations of how clients talk about their psychological distress will contribute to your final decisions.

Final Decisions

Using a traditional assessment approach, you can estimate your client’s suicide risk as fitting into one of three categories:

- Minimal to Mild: Client reports no suicidal thoughts or impulses. Client distress is minimal. Plan: Monitor client distress. If distress rises, or depressive symptoms emerge, re-assess for suicidality.

- Moderate to High: Client reports suicidal ideation. As client distress, planning, risk factors, and intent increase, risk increases. Plan: Manage the situation with a collaborative safety plan. Depending on client preference, engaging family or friends as support may be advisable. Make sure firearms and lethal means are safely stored.

- High to Extreme: Client reports suicidal ideation, plans, multiple risk factors (likely including a previous attempt), intent, and has access to lethal means. Engagement in treatment is minimal to non-existent. Plan: Treatment may include hospitalization and/or intensive outpatient therapy with a safety plan implemented in collaboration with family/friends. Make sure firearms and lethal means are safely stored.

************************

As always, please share your thoughts in the comments on this blog.

I just finished reading this chapter today for class. (And then I went outside and touched grass.) Thank for humanizing this topic. I appreciate the realness, and I’m excited to find your writing!

Thanks Bonnie! I appreciate your kind and supportive feedback. JSF